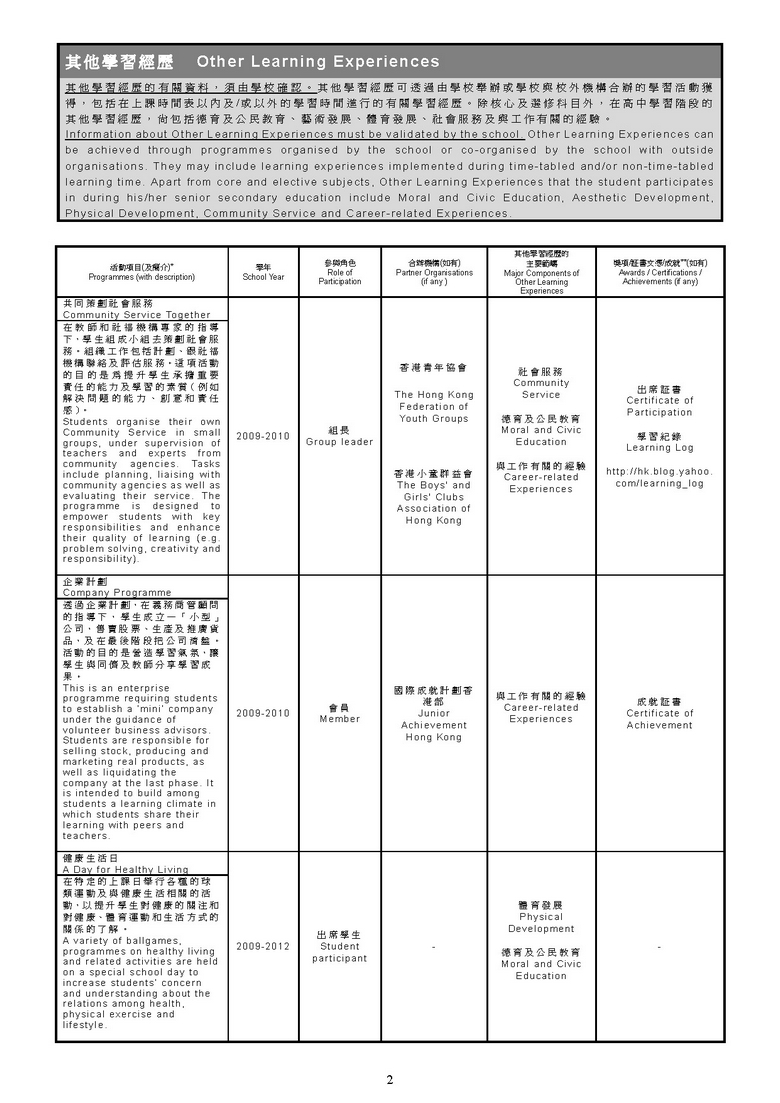

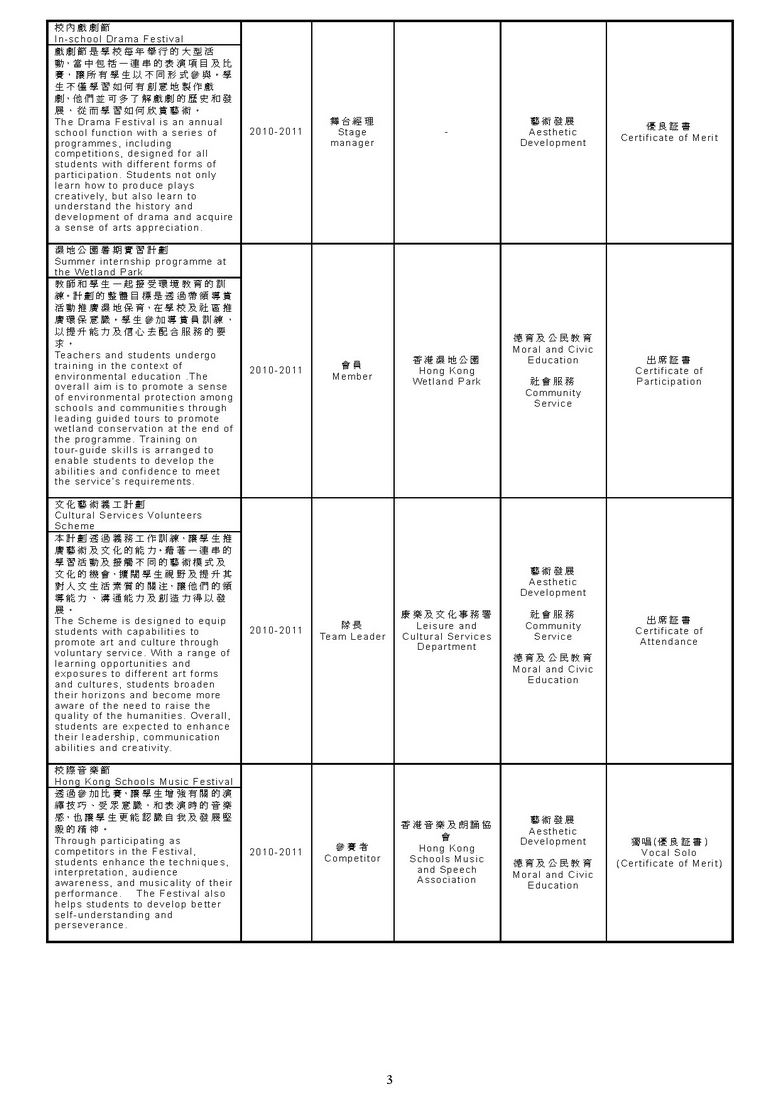

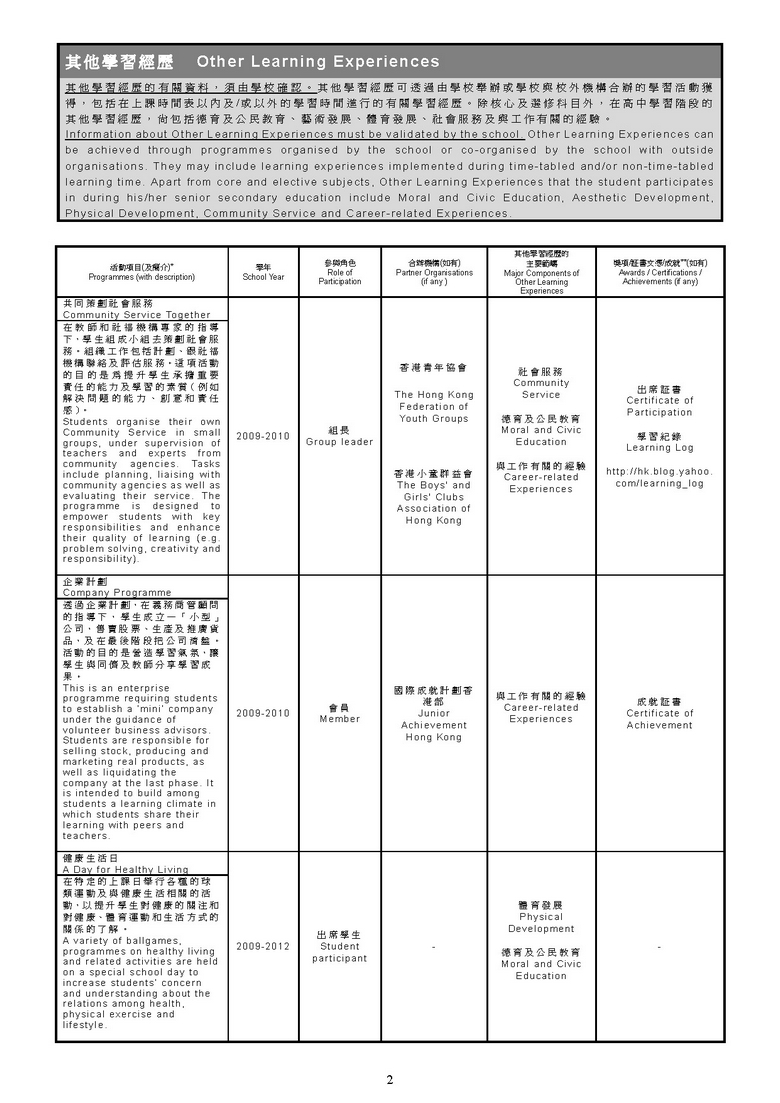

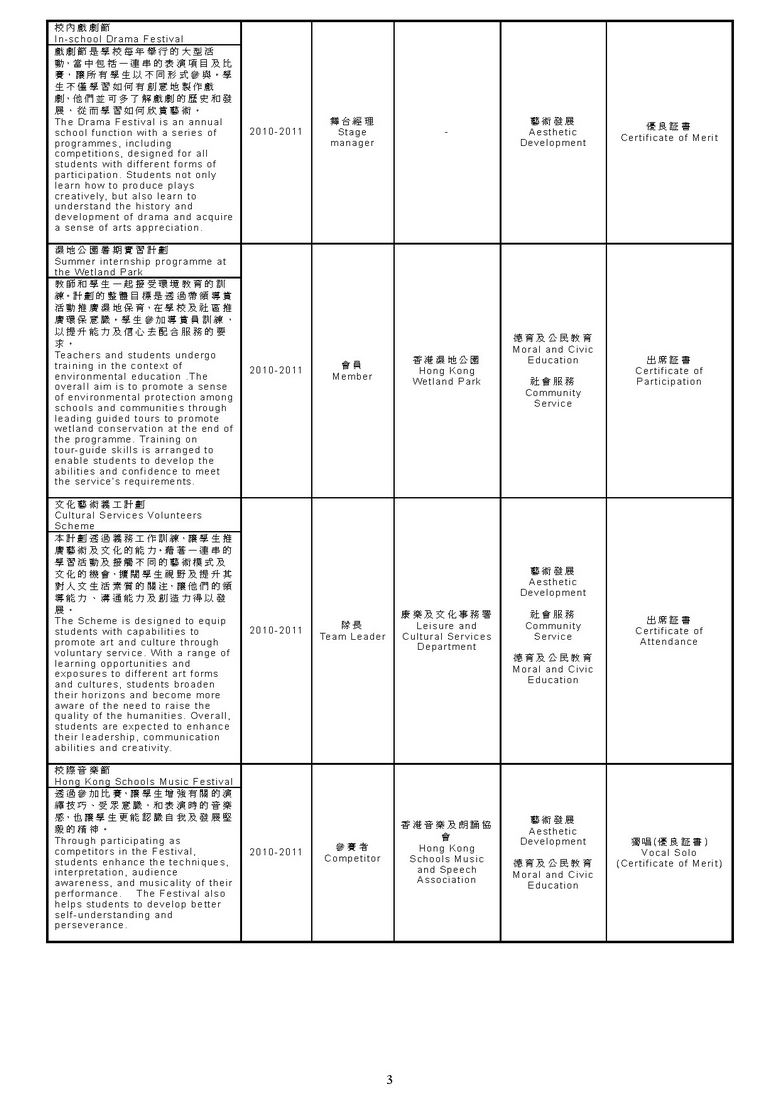

Other Learning Experiences is one of the three major components of the Senior Secondary curriculum that complements the core and elective subjects (including Applied Learning courses and other languages) for the whole-person development of students. These experiences include Moral and Civic education, Community Service, Career-related Experiences, Aesthetic Development and Physical Development.

The senior secondary curriculum framework is designed to enable students to attain the seven learning goals for whole-person development and stretch the potential of each student (i) to be biliterate and trilingual with adequate proficiency; (ii) to acquire a broad knowledge base, and be able to understand contemporary issues that may impact on their daily life at personal, community, national and global levels; (iii) to be informed and responsible citizen with a sense of global and national identity; (iv) to respect pluralism of cultures and views, and be a critical, reflective and independent thinker; (v) to acquire information technology and other skills as necessary for being a life-long learner; (vi) to understand their own career/ academic aspirations and develop positive attitudes towards work and learning; and (vii) to lead a healthy lifestyle with active participation in aesthetic and physical activities.

HKDSE is the qualification to be awarded to students after completing the three-year senior secondary curriculum (to be implemented in 2009) and subsequently taking the public assessment.

Its purpose is to provide supplementary information on the secondary school leavers’ participation and specialties during senior secondary years, in addition to their academic performance as reported in the Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education, including the assessment results for Applied Learning courses, thus giving a fuller picture of students’ whole-person development.

| Booklet 5B |

Student Learning Profile – Celebrating Whole-person Development |

|

| |

| This is one of a series of 12 booklets in the Senior Secondary Curriculum Guide. Its contents are as follows: |

Contents |

| 5.1 |

Purpose of the Booklet |

| 5.2 |

Purpose of Student Learning Profile |

| 5.3 |

Content of Student Learning Profile |

| 5.4 |

School-based Student Learning Profile: Design and Implementation |

| 5.5 |

Examples of Student Learning Profile Implementation Practices |

| 5.6 |

Tools for Student Learning Profile |

| 5.7 |

Key Issues related to School-based Student Learning Profile |

| Appendices |

| References |

|

| |

| 5.1 Purpose of the Booklet |

| |

|

To explain the general aims and concepts of Student Learning Profile (SLP) |

|

To provide guidelines and suggestions on how to develop school-based SLPs by building on schools’ existing strengths |

|

To illustrate different possible practices, approaches and templates/ formats of SLPs to enhance school-based learning and development |

| |

| |

| 5.2 Purpose of Student Learning Profile |

| |

| SLP is a summary record of what students achieve, in terms of their whole-person development (other than their results in the Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education (HKDSE) Examination) during the senior secondary (SS) years.; The purpose of SLP is to provide supplementary information on secondary school leavers’ competencies and specialties, in order to give a fuller picture of the students. Schools need to note the following when introducing SLPs: |

| |

|

Each student should be encouraged to develop an SLP for recording and reflecting on their learning experiences and achievements. Schools should assist students in creating this profile, building on existing practices. |

|

The SLP concept is not new to schools. There are many existing school practices that already serve the purposes of SLP. Schools are advised to further develop existing school-based practices and strengths to help SS students ‘to tell their own stories’ about their participation and achievements. |

|

At students’ discretion, SLPs could be used as documents to demonstrate personal qualities and competence to future employers and tertiary institutions. |

| |

| |

| 5.3 Content of Student Learning Profile |

| |

| To serve as evidence of whole-person development, the content of an SLP may include brief information on: |

|

academic performance in school (other than results in the HKDSE Examination); |

|

Other Learning Experiences (OLE); |

|

performance/ awards gained outside school; and |

|

student’s self-accounts (e.g. highlighting any impressive learning experiences or career goal setting). |

| |

| |

| 5.4 School-based Student Learning Profile: Design and Implementation |

| |

| An SLP is not intended to be another ‘bolt-on’ initiative, but a way of enhancing learning and recognising personal development. Building on existing school-based practices (e.g. school reports, transcripts, portfolios), SLPs can take any form and include any content that helps students to tell their ‘stories of learning’; their participation as well as achievements conducive to whole-person development during the SS years. |

| |

| Schools have flexibility in designing and implementing their SLPs, including: |

|

the content (e.g. appropriate items to be included, such as the five components under OLE (see Booklet 5A)); |

|

the level of detail required; and |

|

the implementation process/ format (e.g. learning portfolio, folder, activity handbook, reflective journal, log book, or data management system). |

| |

| School-based SLP systems can generate concise reports for individuals which are in line with the requirements of tertiary institutions and some employers (See Appendix I for a sample template of SLP in WebSAMS). |

| |

| SLPs should be designed as a summary of student participation and achievements conducive to whole-person development during the SS years (usually not more than a few pages) , rather than an account of each and every detail. It is the quality that matters, not quantity (see Appendix II for "Dos and Don’ts in OLE and SLP"). |

| |

| The content of an SLP also enables students who leave school early to provide useful information to future employers and/ or tertiary institutions if deemed appropriate. |

| |

| |

| 5.5 Examples of Student Learning Profile Implementation Practices |

| |

| There is already a wide range of good school practices that achieve the purposes of SLP, although such practices may vary among schools. Schools are advised to decide on a school-based ‘starting strategy’ as an entry point to implement SLPs, before adopting any particular tools. This could be done through reviewing and building on their existing practices. The following sets out some implementation procedures which schools might consider adopting as their SLP starting strategies. |

| |

Figure 5.1 Four Starting Strategies of SLP Implementation |

|

| |

| In general, schools might consider two possible routes of implementation,

teacher-driven route and student-led route, when deciding on their SLP

‘starting strategy’: |

| |

| Teacher-driven route |

| |

| Building on existing strengths with a well-established data management system and effective clerical support, schools could assist students in building their profiles by collecting relevant data for them (including both ‘academic performance’ and ‘OLE information’). Under teacher guidance, students could be asked to select what they would like to put in their SLPs. Students might also include additional items (e.g. awards gained outside school) at their discretion. |

| |

| Example: |

Using a Web-based Data Management System to Build the SLP – a Recording-oriented Approach |

| |

| A web-based data management system to record OLE data |

| |

| School A set up a simple but effective data management system to handle records of student participation in extra-curricular and personal development activities in 1998. The system helped teachers to handle the information that eventually developed into a very large number of print documents. A link with WebSAMS was later established so that the system could help to formulate non-academic records. Having got used to operating this system, teachers found their record-keeping workload greatly reduced. The data captured were used to generate school-based SLP or transcript for every student. In the process, students were also encouraged to discuss their SLPs with career teachers and select appropriate items, such as OLE and achievements outside school, for inclusion in their profiles in the final year of SS education. |

| |

| Building on these school practices, the school decided to use the SLP module of WebSAMS to help students to build their profiles at the SS level. As a long-term strategy, the school also plans to enhance student involvement in building their profiles by enhancing the role of class teachers. Half-yearly discussions and de-briefings with students will be arranged. To create space for teachers and students, a number of class teacher periods will be used to help students to set learning goals for their own all-round development, review their participation, and select ‘key’ learning experiences for reporting. Clerical support will also be provided to input data provided by teachers. |

| |

| The school believes that these arrangements best fit the school culture and strengths. Without the need to consider any start-up and maintenance cost, the school also finds the selected approach and arrangements cost-effective. |

|

|

| |

Example: Using a Web-based Central Record System to Build the SLP – a Reflection-Oriented Approach |

| |

| Promoting reflection to help students to turn experiences into learning during the SLP building process |

| |

| Michael is an SS student in School B. The life education teacher has been a mentor for his whole-person development. He recorded his OLE and outside school activities in a student handbook and selected a number of impressive activities to provide more in-depth reflection. This handbook has been used as a tool for him to interact with his teacher. Based on the information provided, the teacher gained a more thorough understanding of Michael’s participation and development. Constant reviews with Michael of his OLE participation and achievements were also arranged. At the end of every school year, the school gave clerical support to input Michael’s activity records into the WebSAMS. He then selected the OLEs that could best represent his development throughout his SS education. Meanwhile, he also supplied information about his outside school activities, using a record list in spreadsheet format, together with a personal self-account. Based on the information inputted and selected in WebSAMS, School B was able to generate an SLP with appropriate content for each student, at any time. |

| |

| The above approach and practices adopted by School B demonstrate that while there is an intention to turn students’ experiences into learning, a reflection-oriented approach can be incorporated into the SLP building process. Without introducing any expensive tool, no additional cost has thus been incurred. However, for sustainability, School B has decided to create space for both teachers and students by using class teacher periods for the sharing of experiences and reflections on learning. As is its existing practice, clerical support will be provided in terms of data input. |

|

|

| |

| Student-led route |

| |

| Some schools have been developing portfolio systems, learning diaries and activity handbooks for years and their students are generally accustomed to building their own profiles by recording relevant data during their SS education. Teachers in some schools may make regular checks on the progress of individual profile building. Such a practice could be conducted with or without an emphasis on student reflection. |

| |

| Example: |

Making Good Use of the School Intranet System –

a Student-led, Recording-oriented Approach |

| |

| Increasing student ownership through building SLPs with the school intranet system |

| |

| Students of School C have used the school intranet system to process data about their development over the years. While the teachers were previously in charge of overseeing data input in the system, the school decided to increase student ownership of their profiles by opening up channels for students to collect and input data themselves. To start small, students were each given a booklet to record their OLEs. Under teachers' guidance during two time-tabled periods, they then entered information about their OLE participation into the school intranet system in order to generate their individual SLP reports. So far, students of School C have been trained to make good use of their own profiles to review their own participation and achievements. |

| |

| For sustainability, School C has planned to provide more space for teachers and students to further develop the SLPs. Apart from the existing two time-tabled periods, a number of class teacher periods will be arranged for SLP-related activities such as selecting ‘key’ learning experiences and sharing of learning with peers and teachers. School C has also taken practical steps to facilitate teacher validation of students’ entries. For instance, ‘teacher-preset items’ covering names and descriptions of the OLE programmes, together with some ‘pull-down menus’, will be prepared for students to retrieve when processing and inputting their own information. The existing resources of the school will also be used to slightly revise the existing system so that it is better aligned with the SS curriculum. |

|

|

| |

| Example: |

Using an Electronic Portfolio System to Build up the SLP - a Student-led, Reflection-oriented Approach |

| |

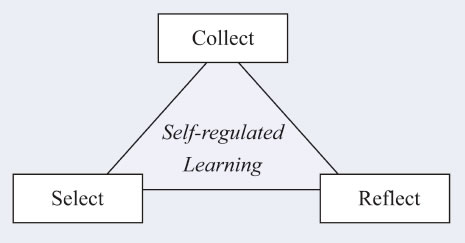

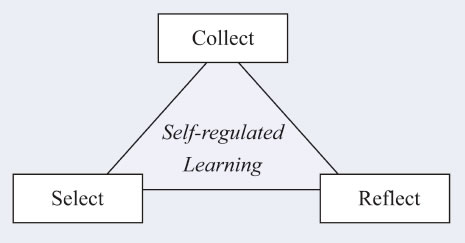

| Cheryl’s case of building SLPs with a student-led and reflection-oriented approach: Encouraging Self-regulated Learning |

| |

| Cheryl was is an SS student in School D. Throughout her SS schooling, Cheryl participated in a variety of school-organised OLE activities, such as a National Education programme and community services. The school made use of an electronic portfolio system to help Cheryl to build her learning profile effectively. During this process, Cheryl was encouraged to make a plan for personal development, provide information about her OLE participation, and reflect on her learning and achievements. Cheryl also provided data and self-reflection on activities that were not organised by the school. Before generating her SLP report, she was also given the opportunity to select the items she wished to see in it. According to Cheryl, she really “owns” her SLP. |

| |

| Apart from its reporting function, the SLP was meaningful to Cheryl because it encouraged self-regulated learning. Assisted by an interactive, user-friendly electronic system, teachers-in-charge found the SLP helpful in providing feedback on Cheryl’s plan and participation. With timely feedback and guidance from teachers, she improved her planning and involvement in her education.; Based on these experiences and development, Cheryl completed her ‘self-account,’ highlighting her strengths, ambitions and future plans. |

| |

| Since an electronic system has been used for a number of years in School D, both teachers and students have become used to its operation and workflow. In recognition of its existing practices that can also reach SLP objectives, School D will continue to help students to build their profiles without any extra cost. Based on previous experience, school D realises the importance of providing opportunities for conducting SLP-related activities under teachers' guidance. For sustainability, time-tabled lessons (e.g. class teacher periods) will be arranged to consolidate learning and enhance reflective thinking. |

| |

|

| |

| For tools and school examples, please browse (http://www.edb.gov.hk/cd/slp/tools) |

| |

|

|

| |

| The four examples indicate above that, when selecting a ‘starting strategy’ to implement SLP, schools should build on their existing practices because they can offer: |

| |

|

shared understanding about the notion of whole-person development; |

|

related experiences that can be developed further; |

|

established structures that can help both teachers and students to develop SLPs (e.g. the existing data management system/ tool); and |

|

knowledge about existing gaps and the direction that can be taken for sustainable development. |

| |

| |

Reflective Questions |

| |

To identify a school-based strategy as an entry point for SLP implementation, the following questions could be discussed among school leaders and teachers: |

| |

|

How does your school record the subject-related and non-subject-related achievements of students to capture their whole-person development? How can teachers and students make use of this data and information? |

|

| |

|

Does your school have any tools (e.g. electronic systems) for students to record their participation and reflections for their SLPs? |

|

| |

|

How can you build on your current practices to help your students to tell their stories about whole-person development? What would be your short-term plan to implement SLPs? |

|

| |

|

Building on existing practices and strengths, which ‘starting strategy’ could your school adopt as an entry point to implement SLPs? |

|

| |

|

Which implementation route is more suitable for your school, teacher-driven or student-led? Why? |

|

| |

|

What SLP tool(s) is/ are appropriate for your school to accomplish the aims of your selected ‘starting strategy’? |

|

| |

|

What arrangements can your school make to ensure sufficient space/ opportunities to implement SLPs (e.g. creating space for teacher support and guidance)? |

|

| |

|

How can your school make good use of existing resources to ensure cost-effectiveness? |

|

| |

|

What are the professional development needs of your teachers in order for them to ensure quality student involvement in preparing SLPs? How are you going to address them? |

|

| |

To plan ahead for the sustainable development of SLPs, schools need to consider the following: |

| |

|

How would you plan to enhance student motivation, ownership and responsibility in school-based SLP development in the long run? What would be your school’s long-term plan for SLPs? |

|

| |

|

How would your school build capacities at student, professional and systemic levels to secure and sustain these targets? |

|

|

| |

| |

| 5.6 Tools for Student Learning Profile |

| |

| Tools for SLPs, if appropriate and cost-effective, could help schools and their students to build profiles. These tools could be sophisticated electronic systems or print-based handbooks, depending on the school’s needs and situations. However, instead of merely focusing on the technical arrangements, the educational values of using the tools in the SLP building process to enhance students’ balanced development should be highlighted. |

| |

| There are many different kinds of tools available for consideration, such as electronic systems for recording SLP information, e-portfolio systems and booklets. These tools are not exhaustive or exclusive. Schools are encouraged to consider the following when selecting them. |

| |

|

Building on existing practices – Schools should review their existing strategies in respect of the need for balanced developments of students; identify strengths and gaps, and carry out long-term planning in order to develop school-based SLPs that will address students’ needs for whole-person development. |

|

Examine the use of IT among teachers and students – This can inform schools about the feasibility of the operation and workflow of the tool selected. For example, if a school has a long history of using IT in their daily learning and teaching, it will be easier for it to adopt the use of new electronic systems for both students and teachers. On the other hand, if a school wants to develop students as active, self-directed learners but the IT culture in school is not strong enough, it may be more desirable for the school to use print-based handbooks (or ‘box file’ portfolios) as

a start, to help students to develop their habits and enhance their sense of ownership. |

|

Appropriate features and functions – The tools, or a combination of tools, should provide features that facilitate the building of SLPs with basic data including students’ particulars, academic performance and OLE information. Tools that allow schools to generate SLP reports with appropriate or selected contents from the database, whenever needed, would also be most desirable. Schools are recommended to make reference to the SLP template of WebSAMS (see Appendix I) when devising the tool. |

|

User-friendliness – Tailor-made features that will enhance the user-friendliness of the tool are definitely assets that will assist in profile building. Examples may include ‘teacher-preset items’ and ‘pull-down menus’ mentioned in the example of School C in 5.5. |

|

Cost-effectiveness – Start-up and maintenance costs are key considerations to ensure SLP sustainability in a school. Quality SLP implementation does not necessarily imply expensive tools. |

| |

An Example of a Tool – an SLP Module of WebSAMS |

| |

| WebSAMS has been enhanced to provide an SLP module to support the implementation of SLPs. The key features are documented below for school reference (Also see Appendix I for its template): |

| |

| Features |

Rationale |

Data management |

|

Space for students’ voice |

A record of OLE information could be generated for students’ reference. Students could review their own participation to see if they would be able to achieve a balanced and all-round development in school education. Students could also select and arrange their favourite OLE activities for presentation in the SLP report.

Students could optionally provide outside school activity information and self-accounts in presenting their views of their own personal development. |

Support for school planning and development |

Schools could also extract relevant OLE data to review students’ participation and the school's provision of OLE to see if the provision could meet the needs of students or not. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

| 5.7 Key Issues related to School-based Student Learning Profile |

| |

| Irrespective of different school-based implementation routes and approaches, there are some key common issues that schools need to note: |

| |

|

SLP leadership – Instead of deploying a Computer/ IT teacher to be wholly responsible for SLP development and implementation, it is advisable for schools to exercise distributed leadership when implementing SLP. By doing so, both senior and middle managers of a school will be involved in terms of SLP leadership and could work as teams. |

|

Purpose – Schools may consider how SLPs may be used as tools to achieve school goals relating to student development, such as those stated in the School Annual Plan and School Development Plan. Schools should make appropriate synergies with the existing ‘form teacher’ structure and/ or on-going careers education programmes to address students’ needs. The core purpose and value of SLPs should be more about celebrating students’ efforts and achievements in their whole-person development, rather than an over-emphasis on their instrumental values (e.g. university admission). |

|

Content – Instead of keeping very detailed records, students should be guided to learn to put entries in their SLP periodically and selectively. |

|

Time for SLP activities – Time and space should be given for both teachers and students to conduct SLP activities. For example, a school might set aside two half-days per year to enable form teachers to discuss with their students their SLPs and their personal development. Alternatively, some schools might use some of the form teacher periods to help students to build their own SLPs when appropriate. |

|

Validation – Schools are expected to keep and verify records of students’ activities as in their existing school report practices. For learning programmes not organised by the school during SS education, students may provide the information to the school. However, it is not necessary for the school to validate such information. Students will be responsible for providing evidence to relevant persons whenever requested. If these activities are included in SLPs, they should be listed in a separate column/ section from the main OLE list. |

|

Use of SLP data – In addition to keeping individual student’s record of whole-person development, schools may use the SLP data of student participation and achievements to inform school planning. |

|

Generation of SLPs – Although an SLP is required to be produced as a summary record at the end of secondary education, it is not advisable for schools to generate SLPs only at the end of the three years of SS education. Schools may consider providing interim profile information at regular intervals (e.g. twice every year) to facilitate the provision of progress feedback and to celebrate students’ success and participation. |

|

Using electronic systems - Electronic systems are often chosen as a means of building up school-based SLPs. Although there are many strong reasons for adopting an ‘e-system’ rather than a print-based system, schools should examine their existing conditions (e.g. culture, facilities, teacher capacities and habits, current practices, clerical and technical support) carefully before opting for an electronic means as described in 5.6. |

|

Dialogic process – According to many success stories, both local and overseas, SLPs are best conducted through maintaining a dialogic process between students and teachers or ‘mentors’ (e.g. business mentors, alumni, parents). The success of SLPs often depends on the quality of interaction/ dialogue between students and teachers/ mentors, rather than the quality of the profile design. For example, some schools managed to run successful programmes through creating time and space to facilitate such teacher-student dialogues. |

|

Students tell their own stories - As students are the ultimate owners of their SLPs, schools should seek to increase students’ sense of responsibility and ownership for their SLPs, regardless of the school-based approaches adopted. Any inappropriate disclosure of content without students’ agreements should be avoided. |

|

Ethics - Teachers should encourage students to include items in their SLPs honestly and ethically since the SLPs are, in many ways, both formative and summative tools for all-round development. In addition, future readers, such as employers, may ask about the content or may request further evidence of certain items in the SLP. The process of building an SLP could be a worthwhile learning experience for our students, which enables them to compile high-standard and reliable curriculum vitaes in their future career life. |

| |

|

| |

| SLPs are best implemented through a whole-school approach when teachers and students treat it as a long-term strategy in promoting whole-person development. The example below illustrates how a school progressively builds up a sustainable practice for SLPs, by cultivating a strong reflective culture among key stakeholders. |

| |

| Example: |

Using Student Portfolios to Nurture Reflection – Building on Existing Strengths |

| |

| Since 2001, School E has been using Student Portfolios as a means of motivating students to reflect on their own learning and personal development. A print-based portfolio has been designed which relates to every aspect of school life and which made available to every student at the beginning of the term, so that they can input the details of their participation and reflections on their own learning. The portfolio system not only enables students to reflect on what has happened but also helps them to plan their future learning and development. At the same time, teachers are also encouraged to engage in reflection through a teacher portfolio, so as to develop a reflective culture within the school. |

| |

| A list of attributes and capabilities to help students and teachers to reflect is also provided. Teachers have to interview students three times a year and provide them with feedback, using the information inside the portfolio. Students are encouraged to reflect alongside their teachers and every student is required to prepare an annual portfolio of his/ her reflections as part of the school’s formal practice. |

| |

| At the beginning, students were found to be quite passive and unmotivated. Teachers had to spend a great deal of effort to encourage them to reflect and build their portfolios. Gradually, the school has managed to build up a very strong culture of reflection for continual improvement. Students are willing to share their reflections on the school web. |

| |

| The practice of reflection is not only applied to learning and teaching in this school. It is also practised by the in school management. An electronic portfolio system will be tried out to see if it might yield a similar impact on student learning. This system will serve as a tool to generate the school-based SLPs. |

|

|

|

| |

| Please visit the website on SLP (http://www.edb.gov.hk/cd/slp) for more information. |

| |

|

| |

| Appendix I |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Appendix II |

|

| |

| Some Dos and Don’ts in OLE and SLP |

| |

Dos |

Don’ts |

| The aim of OLE is to help students to develop as life-long learners with a focus on sustainable capacities, with expected outcomes such as: |

|

becoming active, informed and responsible citizens |

|

developing respect for plural values and interests in the arts; |

|

adopting a healthy lifestyle; and |

|

enhancing career aspirations and positive work ethics. |

|

The aim of OLE is NOT to produce a presentable SLP, with detailed records of activities attended by the individual. |

OLE and SLP must be built on schools’ existing practices and strengths. |

OLE and SLP DO NOT necessarily mean re-designing everything or abolishing existing good practices, e.g. reducing PE lessons and extra-curricular activities or adopting a completely new e-portfolio system. |

It is the quality, rather than the quantity that matters in OLE. Schools should concentrate on offering programmes that could motivate students and facilitate deep reflection. |

Meeting the suggested time allocation should NOT be the most important or the only aspect in the overall planning for OLE. Furthermore, the number of students’ OLE records should NOT be the essence of the design of school-based SLP. |

Regular and structured learning opportunities (e.g. timetabled lessons) are the essential forms of implementation of Physical Development (PD) and Aesthetic Development (AD), in terms of meeting their objectives and expected outcomes. |

AD and PD should NOT be implemented merely through co-curricular/ extra-curricular activities or one-off special school days. |

Student reflection is crucial in OLE. It could be manifested or expressed in a wide range of forms in OLE contexts, such as journals or ‘blog’ writing, worksheets, tape recording own thoughts, talking with peers, Power-Point presentations, group discussions in de-briefings, drawings, designing a short play with a target audience or producing a promotional video collectively. |

Reflection can be simply interpreted as enabling a person to ‘step back and think’ upon an experience. In this sense, reflection in OLE does NOT mean asking students to reflect in written form (e.g. reports, notebooks) after every activity. |

SLP should be best implemented to encourage student reflections on their own personal development and should be seen as an opportunity for students to ‘tell their own stories of learning’. |

SLP should NOT be seen merely as detailed records of all the participation and achievements of individuals. Students should be given opportunities and guidance to select appropriate items to be included in the final profiles. Profiles should be simple, concise and easy to read. |

Schools should devise suitable arrangements for SLP, building on existing practices. |

SLP does NOT necessarily imply adopting a ‘powerful and expensive’ electronic system to yield desirable educational aims. |

SLP is designed for students to tell their ‘stories of learning’ and to celebrate their successes, in terms of whole-person development. |

While SLP will be used as a reference document during university admission, it could provide a fuller picture of the students’ competencies and specialties for consideration. However, the purpose of an SLP is NOT solely for university admission. |

OLE (and SLP) requires strong connected and learning-centred leadership that clearly communicates the need for change so that teachers from different areas can both understand and play an active part in planning and developing the OLE programmes. |

The leadership of OLE and SLP should NOT rest solely on the OLE / SLP co-ordinator. OLE should NOT be planned as if it is a disconnected, add-on school initiative, without fostering effective links with other projects and components of the curriculum. |

Schools will assist students in developing their SLPs. This will be an educational process for students to select and review on their participation, and to address their whole-person developmental needs. |

OLE is part of the SS curriculum in school. Students are thus offered sufficient opportunities of OLE to promote whole-person development and enhance quality of life. Parents need NOT make extra efforts to arrange more OLE just for the sake of quantity, or to build profiles for their children. |

|

| |

| |

| References |

| |

| Publication |

| |

| Assiter, A. & Shaw E. (1993). Using Records of Achievement in Higher Education. London: Kogan Page. |

| |

| Axelrod, R. (1990). The Evolution of Co-operation. London: Penguin. |

| |

| Costa, L A. & Kallick, B. (2000). Assessing and Reporting on Habits of Mind. USA: The Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. |

| |

| Covington, M.V. (1984). The motive for self-worthin Ames, R & Ames C (ed) Research on Motivation in Education, Vol 1: Student Motivation. London: Academic Press. |

| |

| Csikszentmihalyi. (1993). The Evolving Self: a Psychology for the Third Millennium. New York: Harper Collins. |

| |

| Curriculum Development Council. (2002). Basic Education Curriculum Guide: Building on Strengths (Primary 1 – Secondary 3). Hong Kong: Education Department. |

| |

| Feuerstein, R. et al. (1980). Instrumental enrichment: an intervention program for cognitive modifiability, Baltrimore. MD: University Park Press. |

| |

| Hall, J. & Powney, J. (2003). Progress File: An Evaluation of the Demonstration Projects, DfES Research Report No. 426. London: Queen’s Printer. |

| |

| Hargreaves, A. (1986). ‘Ideological record breakers?’ in Broadfoot, P. (ed.) Profiles and Records of Achievement. Holt: Sussex. |

| |

| Juvonen, J. & Wentzel, K. (1996). (eds) Social motivation: understanding children and school adjustment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

| |

| Karniol, R. & Ross, M. (1996). The motivational impact of temporal focus-thinking about the future and the past, Annual Review of Psychology, 47: 593-620. USA: Annual Reviews. |

| |

| Lazear, D. (1999). Multiple Intelligence Approaches to Assessment: Solving the Assessment Conundrum. USA:Zephyr Press. |

| |

| Miller, A. (1998). Business and Community Mentoring in Schools (DfEE Research Report 43). London: DfEE |

| |

| Nisbet, J. & Shucksmith J. (1984). The Seventh Sense. Scottish Educational Review, 16, 75-87. |

| |

| Sarason, B. R. et al. (1990). Social Support: The sense of acceptance and the role of relationships. In Sarason, B R et al (eds) Social Support: An Interactional View. New York: John Wiley & Sons. |

| |

| Stoll, L. et al. (2003). It’s About Learning (and It’s About Time). London: Routledge Falmer. |

| |

| Tierney, J. P. et al. (1995). Making a Difference: an Impact of Study of Big Brothers/ Big Sisters. Philadelphia, PA: Public/Private Ventures. |

| |

| Watkins, C. (2000). ‘Now just compose yourselves’ ― personal development and integrity in changing times. Watkins, Lodge & Best (ed.) Tomorrow’s Schools - Towards Integrity. London: Routledge Falmer. |

| |

| Zimmerman, B. J. et al. (1996). Developing Self-regulated Learners: Beyond Achievement to Self-Efficacy. USA: The American Psychological Association. |

| |

| Website |

| |

Students telling their own “stories of learning”: A multiple case study on the implementation of Student Learning Profile (SLP). Hong Kong Education Bureau

(http://www.edb.gov.hk/cd/ole/ole_articles/). |

| |

|