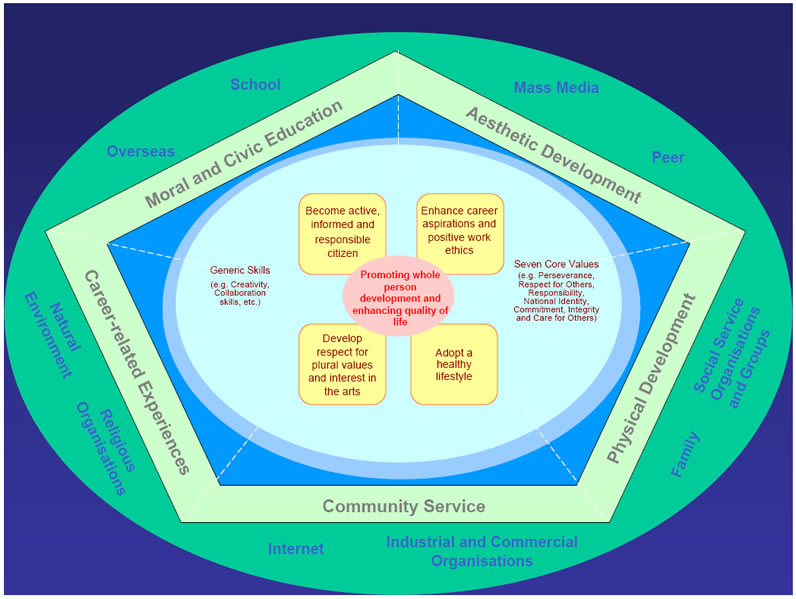

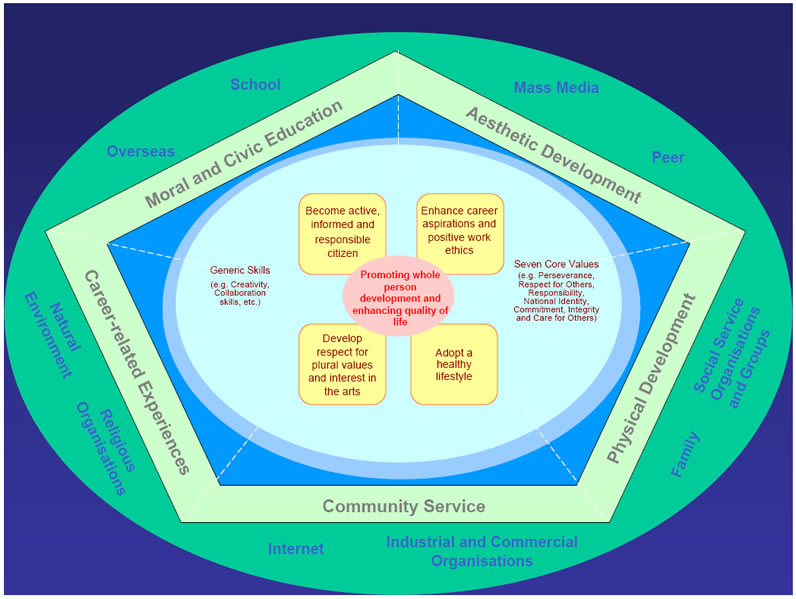

Other Learning Experiences is one of the three major components of the Senior Secondary curriculum that complements the core and elective subjects (including Applied Learning courses and other languages) for the whole-person development of students. These experiences include Moral and Civic education, Community Service, Career-related Experiences, Aesthetic Development and Physical Development.

The senior secondary curriculum framework is designed to enable students to attain the seven learning goals for whole-person development and stretch the potential of each student (i) to be biliterate and trilingual with adequate proficiency; (ii) to acquire a broad knowledge base, and be able to understand contemporary issues that may impact on their daily life at personal, community, national and global levels; (iii) to be informed and responsible citizen with a sense of global and national identity; (iv) to respect pluralism of cultures and views, and be a critical, reflective and independent thinker; (v) to acquire information technology and other skills as necessary for being a life-long learner; (vi) to understand their own career/ academic aspirations and develop positive attitudes towards work and learning; and (vii) to lead a healthy lifestyle with active participation in aesthetic and physical activities.

Values constitute the foundation of the attitudes and beliefs that influence one’s behaviour and way of life. They help to form the principles underlying human conduct and critical judgement, and are qualities that learners should develop. Some examples of values are rights and responsibilities, commitment, honesty and national identity. Closely associated with values are attitudes. The latter supports motivation and cognitive functioning, and affects one’s way of reacting to events or situations. Since both values and attitudes significantly affect the way a student learns, they form an important part of the school curriculum.

ApL is an integral part of the three-year senior secondary curriculum. It takes broad professional and vocational fields as the learning platform to develop students’ foundation skills, thinking skills, people skills, positive values and attitudes and career-related competencies, in order to prepare them for further study/ work as well as life-long learning. ApL courses complement the senior secondary subjects, adding variety to the senior secondary curriculum.

Generic skills are skills, abilities and attributes which are fundamental in helping students to acquire, construct and apply knowledge. They are developed through the learning and teaching that takes place in different subjects or Key Learning Areas, and are transferable to different learning situations. Nine types of generic skills are identified in the Hong Kong school curriculum, i.e. collaboration skills, communication skills, creativity, critical thinking skills, information technology skills, numeracy skills, problem-solving skills, self-management skills and study skills.

Its purpose is to provide supplementary information on the secondary school leavers’ participation and specialties during senior secondary years, in addition to their academic performance as reported in the Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education, including the assessment results for Applied Learning courses, thus giving a fuller picture of students’ whole-person development.

| Booklet 5A |

Other Learning Experiences – Opportunities for Every Student |

|

| |

| This is one of a series of 12 booklets in the Senior Secondary Curriculum Guide. Its contents are as follows: |

Contents |

| 5.1 |

Purpose of the Booklet |

| 5.2 |

Values Education and Learning Experiences as Part of Learning Goals in Senior Secondary Education |

| 5.3 |

Aims and Expected Outcomes of Other Learning Experiences |

| 5.4 |

Planning and Time Arrangement of Other Learning Experiences |

| 5.5 |

Guiding Principles for the Running of a School-based Other Learning Experiences Programme |

| 5.6 |

Other Learning Experiences as a Means to Helping Whole-person Education and Balanced Development |

| 5.7 |

Harnessing Community Resources |

| 5.8 |

Student Reflection as a Key to Success |

| 5.9 |

Appraising Student Performance in Other Learning Experiences |

| Appendices |

| References |

|

| |

| 5.1 Purpose of the Booklet |

| |

|

To set clear aims and expected outcomes for Other Learning Experiences (OLE) |

|

To provide guidance on how to achieve a better balance between academic and personal development for young people through offering OLE opportunities in schools |

|

To illuminate the guiding principles for the running of a school-based OLE programme |

| |

| |

| 5.2 Values Education and Learning Experiences as Part of Learning Goals in Senior Secondary Education |

| |

| How do teachers help their students to acquire and practise positive values? How do they prepare them to face the challenges of a world of work and adult life, which is constantly changing? In the document Learning to Learn – Life-long Learning and Whole-person Development (CDC, 2001) (containing the overall framework of the school curriculum), there are three interconnecting components: |

| |

|

Knowledge and concepts (mainly through subject teaching) |

|

Generic skills |

|

Values and attitudes. |

| |

| Of these three, positive values and attitudes are the most difficult to ‘teach’ as subjects because they are best developed through personal experiences in which particular values and attitudes are practised and discussed. OLE, which aim to bridge this gap in the senior secondary (SS) curriculum, are building on the foundations of the five Essential Learning Experiences in Basic Education (CDC, 2002). They put more emphasis on choices, interests, individual needs and personal aspirations to realise whole-person development. |

| |

| If the balance of personal development is to be achieved, students should be encouraged to participate in all five areas of OLE, namely Moral and Civic Education (MCE), Aesthetic Development, Physical Development, Community Service and Career-related Experiences. This means that schools should, as far as possible, offer students a range of OLE opportunities, both within and outside normal school hours. |

| |

| |

| 5.3 Aims and Expected Outcomes of Other Learning Experiences |

| |

| In implementing OLE, teachers need to keep the following aims and expected outcomes in mind: |

|

To widen students’ horizons, and to develop their life-long interests |

|

To nurture positive values and attitudes |

|

To provide students with a broad and balanced curriculum with essential learning experiences alongside the core and elective components (including Applied Learning (ApL) courses1) in order to nurture the five essential Chinese virtues, ‘Ethics, Intellect, Physical Development, Social Skills and Aesthetics’ (德、智、體、羣、美) |

|

To facilitate students’ all-round development as life-long learners with a focus on sustainable capacities. The expected outcomes include students: |

| |

|

becoming active, informed and responsible citizens; |

| |

|

developing respect for plural values and interests in the arts; |

| |

|

adopting a healthy lifestyle; and |

| |

|

enhancing career aspirations and positive work ethics. |

| |

| It should be borne in mind that OLE are not only a series of school activities or lessons, but also an integral part of the SS curriculum. They help students to build a solid foundation for whole-person development and pursue life-long learning in our knowledge-based society. It is the quality of OLE that matters, rather than the quantity (see Appendix II in Booklet 5B for “Dos and Don’ts in OLE and SLP”). |

| |

| 1ApL was formerly known as “Career-oriented Studies”. Readers may refer to the report “Action for the Future – Career-oriented Studies and the New Senior Secondary Academic Structure for Special Schools” (EMB, 2006) for details. |

| |

| |

Reflective Questions |

| |

|

What are you currently doing in school to address the aims of OLE described above? Which areas are your strengths? |

|

| |

|

What practical steps could you take to address these aims more effectively? |

|

| |

|

How would your school help students and parents to appreciate the importance of OLE, as an integral part of the SS curriculum? |

|

|

| |

| |

| 5.4 Planning and Time Arrangement of Other Learning Experiences |

| |

| The time allocation of OLE over the three years is suggested as follows: |

| |

| Other Learning Experiences |

Suggested minimum time allocation

(in percentage) |

Minimum lesson time (or learning time equivalent) allocation

(in hours) |

| Moral and Civic Education |

5% |

135 |

| Community Service |

| Career-related Experiences |

| Aesthetic Development |

5% |

135 |

| Physical Development |

5% |

135 |

| |

Total: 405 hours |

|

| |

| Schools are encouraged to have an overall and flexible planning of OLE lesson time (including time-tabled and/ or non-time-tabled learning time) for students throughout the three years of SS education. Apart from building on the strengths and experiences the school has already had, due consideration should be given to the suggested modes of implementation for each type of OLE specified in Section 5.6 of this booklet. |

| |

|

| |

Example: Time planning for Other Learning Experiences – Minimum Threshold Approach |

| |

| School A devised a comprehensive plan for OLE, utilising time-tabled lessons, calendar days and co-curricular activities to promote whole-person development among students. In order to check whether their plan satisfied the suggested minimum hours of OLE, teachers, for their own reference, worked on the hours involved by using a so-called ‘minimum threshold approach’. Instead of counting every single activity, they first worked out the number of OLE hours allocated to the time-table which were to be offered to all students regularly.; Then they checked to see if there were any gaps to be filled by OLE-special days or other events that would appear in their school calendar. As a result, the school found that it had already met the suggested time allocation by just counting the OLE provisions in both the time-table and school calendar. OLE teachers in School A then stopped the ‘hour-counting’ exercise and invested time in devising ways to enhance quality and student participation in the overall OLE school plan. |

| |

| Also see the article, “A Self-checking Workflow of OLE Time Arrangement”: |

(http://www.edb.gov.hk/cd/ole/ole_articles/) |

|

| |

| The formation of a co-ordinating team to enhance synergy is suggested in order to plan a school-based programme for OLE. Initial planning could involve: |

| |

|

reviewing any existing strengths; |

|

finding out what is needed; |

|

devising effective communication strategies for stakeholders; |

|

fostering community partnerships and connections; |

|

allocating resources; |

|

planning programmes and devising their evaluation strategies; and |

|

sharing effective learning and teaching strategies. |

| |

| |

| 5.5 Guiding Principles for the Running of a School-based Other Learning Experiences Programme |

| |

| In order to develop a school-based OLE programme, seven guiding principles are suggested for school leaders’ and teachers’ reference. These are shown in Figure 5.1 in which the centrepiece is ‘Building on existing practices’. ;Each of the other six principles is arranged around this central concept to illustrate that it is not about imposing something new but enhancing, re-prioritising or re-conceptualising what already exists. |

Figure 5.1 |

|

| |

| Principle 1: Building on existing practices/ strengths |

| |

| The first principle is observed when schools: |

|

review and build OLE into their existing practices and strengths, as well as identifying ‘gaps’ and ‘over-dos’, and making adjustments accordingly; |

|

avoid ‘re-inventing’ the entire programme or ‘changing just for the sake of change’. For example, based on the suggested time allocation of OLE (at least 5%), schools should fully utilise the learning opportunities provided by existing Physical Education (PE) lessons to enhance student learning in the context of physical development; |

|

clearly communicate the need for change so that teachers both understand and play an active part in planning and developing the OLE programme; and |

|

consider leadership strategies such as distributive leadership and allocate leading responsibilities to teachers for OLE if appropriate. |

| |

|

| |

Example: Building on Existing Strengths |

| |

| Seizing the opportunity to review and re-prioritise |

| |

| With a long history in being a ‘Health Promoting School’, School C was awarded a gold medal in the local Healthy Schools Award Scheme. Building on this strong foundation, the school management used OLE as an opportunity to review the school entitlements with regard to whole-person development under the core value of ‘Healthy School’2. After a discussion with frontline teachers and parents, it was agreed that Community Service would be emphasised more through the existing programmes and Religious Studies periods. Currently, the school expects that in the long run all students will participate with the long-term aim of promoting community health and civic responsibility. In this connection, the school has recently launched anti-drug and healthy eating programmes through placing relevant OLE under its ‘Healthy School’ policy. |

|

|

| |

| 2The ‘Healthy School Award Scheme’, which is run by the Chinese University of Hong Kong, aims to promote the World Health Organisation's concept of ‘Health Promoting School’. |

| |

| Principle 2: Student-focused |

| |

| The second principle starts from where the student is (i.e. his or her prior knowledge, attitudes and experiences) and the nature of experiences that engage interest and facilitate achievement. This principle |

|

emphasises individual active engagement in activities as opposed to a transmission model of knowledge. The focus is on what students experience and how they internalise and make sense of that experience so as to effect a change in personal values and attitudes; and |

|

is more likely to be realised when: |

| |

|

individual participation in OLE is recorded in a learning profile through a school-based system which both recognises achievement and provides motivation; |

| |

|

choices are offered to cater for individual needs, interests, prior experiences and balanced development to increase the sense of ownership; and |

| |

|

student voice and responsibilities are valued in OLE. |

| |

Example: Student-focused |

| |

| Finding what is needed |

| |

| In helping to design the OLE programme, School D conducted annual surveys and focus group interviews among students on their interest in meeting their personal development needs. Ultimately, it was found that the OLE design was ‘in-touch’ with students’ needs and interests. The exercise also helped to foster a better sense of ownership and increased active engagement in whole-person development among students and other stakeholders. |

| |

| Student leadership for serving |

| |

| Students in School E were generally experienced in Community Service in junior secondary levels. In their senior levels, students were asked to organise their own Community Services in small groups, under the supervision of teachers and experts from community agencies. Tasks include planning, liaising with community agencies as well as evaluating their service. It was found that this student empowerment enhanced the quality of learning (e.g. developing problem-solving skills, creativity and responsibility), as well as participation. Participants reported that they were enlightened by such experiences and the impact on them was positive and long-lasting. |

|

|

| |

| Principle 3: Student opportunities |

| |

| The third principle emphasises the need for a well-distributed range of other learning opportunities for all students in a school. Schools need to: |

|

|

provide their students with opportunities in all the five areas of OLE through careful planning, noting the possibilities that more than one area of OLE could be achieved through a single activity; |

|

plan OLE opportunities with a reasonable level of diversity to cater for different individual needs (e.g. one-off ‘taster’ programmes); and |

|

take cautious measures so as not to deprive students from disadvantaged backgrounds (e.g. low-income families) of the opportunities to take part in OLE activities. Cost-benefits and affordability should be considered when planning OLE activities. Expensive activities are not necessarily more effective than those that cost less. |

| |

Example: Student Opportunities |

| |

| Diversified opportunities in Community Service |

| |

| School F’s ‘Volunteer Ambassadors Award Scheme’3 aims to encourage all students to care for others in their communities. In collaboration with Non-government Organisations (NGOs), students were provided with a wide range of service opportunities covering flag days, fund-raising activities, conservation, a junior tutors scheme for local primary students and serving the elderly or disabled. Some activities were specially designed as ‘taster programmes’ for ‘beginners’ and ‘less keen’ students. |

| |

| Monitoring opportunities through a Multiple Intelligence (MI) Passport |

| |

| School G launched an MI passport scheme to motivate each student towards whole-person development, using Gardner’s MI framework. In their passports, students were asked to enter records of their participation and learning with regard to personal development. Form teachers discussed the MI passports with individual students to encourage participation. The gathered information proved to be useful in monitoring OLE opportunities offered and what was ‘missing’ in the school-based programme. In recent years, the school has put more emphasis on creative arts and music in their learning programmes and also in time-tabled lessons to provide sufficient and balanced OLE opportunities. The formative use of the information is highly valued by students and teachers, in terms of school planning and promoting students’ self-regulated learning. |

|

|

| |

| 3The ‘Volunteer Ambassadors Award Scheme’ is a multi-strand school-based programme, which provides bronze, silver and gold awards for students to target at during their secondary years. Students are awarded points for participating in each service activity. |

| |

| Principle 4: Quality |

| |

| The fourth principle reminds us that it is the quality of experience that counts, not quantity. A quality learning experience can sustain or initiate life-long engagement in an area of interest and should comprise the following elements: |

|

strong learning intentions with objectives shared with students, together with the teacher being ready for other ‘unintended but positive’ outcomes |

|

well-organised meaningful learning experiences, embracing a number of factors in the planning, such as students’ prior knowledge/ experiences, learning needs, motivation and safety |

|

programmes run by external bodies or personnel during lesson time and conducted in the presence of registered or permitted teachers in a school |

|

timely de-briefing with teachers as facilitators and deep reflection among students on what they have learnt |

| |

| Besides the quality of individual learning experience, the principle also addresses the following dimensions of looking into the quality of OLE: |

|

the quality of organising OLE at leadership and management level |

|

the quality of organising OLE by creating space and enhancing professional learning |

|

the quality of organising OLE through fostering community partnerships |

| |

| In order to improve the overall organisation of OLE, school leaders need to go beyond the level of individual learning experiences and consider the following: |

|

How well does the OLE programme reflect the core values and uniqueness of the school? |

|

How effective is the organisational process, such as lateral collaboration among initiatives and groups? |

|

How much space and time are given to creating opportunities for both student learning and teachers’ professional learning in the OLE implementation plan? |

|

How well do schools/ teachers understand the notions of community resources and partnership, and the building of strong connections with different kinds of community resources for quality OLE? |

| |

|

| |

Example: Aiming for Quality – at Organisation Level |

| |

| As a member of the EDB Life-wide Learning Network for several years, School I has devised a comprehensive framework to reflect holistically on the quality of their learning programmes both inside and outside classroom/ normal lessons under the following headings. |

| Organising and planning |

Workforce consideration |

1. |

Having a purpose |

7. |

Teacher engagement |

2. |

Finding what is needed |

8. |

Involving students and others |

| |

|

| Leadership for Learning |

Deployment of resources |

3. |

Curriculum links |

9. |

Getting the best from resources |

4. |

Choice/ widening participation |

10. |

Getting the best from partnerships |

5. |

Developing programmes |

|

6. |

Information strategy |

Evaluation strategies |

| |

11. |

Getting results |

| |

12. |

Managing improvement |

| |

13. |

Celebrating success |

| |

|

|

| |

| The school also invited other schools in the EDB Life-wide Learning Network to discuss and evaluate their findings together before devising future action plans. From this example, we may conclude that the quest for quality is now a feature of the on-going school culture when offering OLE to their students. |

| |

| EDB Website of the Quality Framework of Life-wide Learning: |

| (http://www.edb.gov.hk/cd/lwl/qf/ ) |

|

|

| |

| Principle 5: Coherence |

| |

| The fifth principle reminds us that OLE should not be a series of ‘unconnected activities’. Nor should OLE be a disconnected component under the SS curriculum. With OLE as an integral part of the curriculum, schools should therefore: |

|

ensure that the school-based OLE programme is a development of what is offered in basic education and complements other components in the SS curriculum (e.g. ApL, choice of subjects); |

|

try to align OLE with the existing school-based life-wide learning (LWL) strategy and flexible learning time concept, e.g. make OLE part of LWL days or weeks as scheduled in the school calendar and implement OLE during specific sessions of each cycle/ week in the time-table; |

|

note that learning experiences gained through the elective subjects such as Ethics and

Religious Studies, PE, Music and Visual Arts and/ or ApL courses should be counted as helping students to achieve the aims of the respective OLE components. Students could record such experiences in their Student Learning Profile; and |

|

make sure that the provision of OLE opportunities is sufficient and balanced. |

| |

| (Cross-reference: Basic Education Curriculum Guide, Booklet 6 (CDC, 2002), Learning to Learn – Life-long Learning and Whole-person Development (CDC, 2001)) |

| |

Examples: Coherence |

| |

| Forming a co-ordinating team |

| |

| An LWL co-ordinating team was formed to implement the whole-school policy in LWL in School J. In order to ensure effective communication across subjects and departments, the team comprised a deputy head, a guidance mistress, the Extra-curricular Activities Master and some relevant KLA panels as members so that LWL practices could be aligned with OLE at the SS level. |

| |

| OLE as part of the whole curriculum |

| |

| Viewing OLE as an integral part of the SS curriculum, the OLE co-ordinator in School K liaised with all subject panels and teachers to re-organise and match the existing KLA extension activities, such as Community Service, which was extended from Religious Studies, and coupled with OLE components. Apart from enhancing the role of OLE as an integral part in extending, enriching and cimplementing the subject curriculum, teachers on the whole have become more ‘in tune’ with the development of OLE and acquired a holistic understanding of the role played by OLE in the curriculum. |

|

|

|

| |

| Principle 6: Flexibility |

| |

| The sixth principle highlights the importance of flexibility in organising the OLE programmes. Schools can: |

|

plan their OLE flexibly, using a wide range of community resources and combinations of time, place and people; |

|

offer students a range of strategies to enhance the quality of experiential learning, e.g. teamwork, simulation/ role play; and |

|

use an integrated approach by designing a programme (e.g. leadership training, campus TV, dramas) incorporating key elements across the five areas of OLE . |

| |

Example: Flexibility |

| |

| An integrated leadership programme as leverage |

| |

| In order to train students at senior levels to become school leaders in organising co-curricular activities, School L co-organises a four-day leadership camp with a youth agency every year. The programme covers all five components of OLE and ‘potential’ student leaders choose a focused area to exercise their leadership after the camp. Regular reflection sessions are organised in the year to allow deeper sharing among student leaders. The programme has been found to be particularly effective in building an independent learning culture and promoting whole-person development through OLE among other students. |

|

|

| |

| Principle 7: Learning together |

| |

| The seventh principle allows us to see OLE as valuable learning opportunities for teachers, as well as for students. Teachers are encouraged to play the role of facilitating adults in OLE, and to act as learners alongside their students. Teachers can: |

|

observe students working in a ‘non-subject’ context and understand more about individuals’ learning styles and approaches; |

|

use OLE to build their capacities through trying out diversified learning and teaching approaches in different learning contexts; |

|

use OLE to build up stronger collaboration among schools, parents, community and students; and |

|

celebrate the benefits of OLE on student development with stakeholders and the wider community. |

| |

Example: Learning Together |

| |

| Learning together in the Wetland Park |

| |

| Students in School M joined the internship programme at the Wetland Park during the summer holidays. The teacher-in-charge and students underwent training together. The overall aim was to promote a sense of environmental protection among schools and communities through leading guided tours at the end of the programme. The training process inspired not only students, but also the teacher and the park officers about how people learn effectively in the context of environmental education. As a consequence, some students and the teacher volunteered to participate in promotion activities related to wetland conservation. |

| |

| Teaching each other in a school enterprise programme |

| |

| An enterprise programme organised by Junior Achievement Hong Kong4 in School N requested students to establish a ‘mini’ company under the guidance of volunteer business advisors. Students were responsible for selling stock, producing and marketing real products, as well as liquidating the company at the last phase. The teacher-in-charge of the programme was an Economics teacher without much practical trading experience. Instead of being an instructor, he experienced the process as a facilitator and participating member. In addition, a learning climate was gradually created in which students shared their learning with peers and teachers. The experiences engendered reciprocal learning between teachers and students. |

| |

| Celebrating OLE outcomes |

| |

| Schools in a network which aims at promoting experiential learning in the school curriculum were committed to investigating the impact of such learning experiences in a more systematic manner. In order to study its impact on students’ affective and social development (e.g. attitude towards learning, self-concept, attitude towards school and leadership), they had tracked a cohort of students (i.e. S1 in the 2004/05 school year) with different levels of OLE participation since 2004. The impact study was accompanied by focus group interviews among network schools. Tentative findings showed that these essential learning experiences had a significant impact on participating students in terms of affective/ social development and attitudes on learning. These benefits were disseminated and celebrated among stakeholders, especially parents at individual school level. It was found that teachers and community groups also learned a lot through this self-evaluative process. |

| |

Details of the Impact Study can be found on the EDB Life-wide Learning Website:

(http://www.edb.gov.hk/cd/lwl/impact_study/) |

|

|

| |

| 4Junior Achievement Hong Kong is an international, non-profit making agency dedicated to running programmes inspiring and empowering young people to improve the quality of their lives and communities. |

| |

| |

Reflective Questions |

| |

|

In the light of the seven guiding principles and your existing practices, what are your school’s strengths and areas for improvement in terms of OLE implementation? What insights do they give you in planning for school-based OLE approaches? |

|

| |

|

What opportunities and threats does your school have in implementing OLE? How can they help you to devise action plans for the implementation? |

|

| |

|

In what way could your school identify ‘gaps’ and ‘over-dos’ of existing practices for OLE? |

|

| |

|

Among the seven guiding principles, which one is the most difficult to achieve in your school? Do you have any suggestions for tackling this? What may be the best possible ‘entry point’? |

|

|

| |

| |

| 5.6 Other Learning Experiences as a Means to Helping Whole-person Education and Balanced Development |

| |

| The following paragraphs explain briefly the key directions of each area of OLE with school examples, and how each might be implemented to achieve the intended overarching goals and expected outcomes mentioned in Section 5.3 (please refer to Appendices I and II for an overall framework and suggested expected outcomes for each OLE area). |

| |

| Moral and Civic Education |

| |

| Moral and Civic Education is essential in nurturing students’ moral and social competencies, cultivating positive values and attitudes, and developing a range of perspectives on personal and social issues. |

| |

| A holistic approach to developing students’ values and attitudes is recommended through integrating National Education, Life Education, Sex Education, Environmental Education, etc.. The overall aim is to help to promote among students seven priority values, namely: Perseverance, Respect for Others, Responsibility, National Identity, Commitment, Care for Others and Integrity. |

| |

Example: Integrating MCE and Service Learning within OLE |

| |

| A secondary school (School O) in the New Territories integrated MCE and service learning within OLE for S4 students. Service learning was used as a learning strategy to nurture in students positive values and attitudes, including responsibilities, respect for life, commitment, empathy, love and care. Pre-service training sessions and services to the elderly in the community were provided as part of the Life Education lessons. To understand students’ progress and learning effectiveness, pre-service and post-service surveys, programme evaluation and students’ reflection were conducted. Students were found to have taken an active role in planning and implementing the programme. They developed ownership in learning and a sense of empathy, sharing and caring. |

| |

|

|

| |

| Example: Promoting Sustainable Development through MCE |

| |

| A secondary school (School P) took part in the community education programme ‘Save Energy, Save our World’. In the first phase of the programme, talks were co-organised with the Council for Sustainable Development to increase students’ awareness of sustainability and environment. Students were then provided with opportunities to design feasible strategies of saving energy for practice at home. To enhance learning, class teacher periods and MCE lessons were also arranged for students to share experiences and discuss outcomes. In the second phase, students served as ‘Energy Saving Ambassadors’ and produced pamphlets based on their prior learning for distribution and promotion of sustainable development in the community. Finally, students concluded and exhibited their learning through reflection and sharing in a school assembly. They considered this a valuable learning experience on how excessive use of energy could have an impact on the environment and on sustainability. |

|

|

| |

| Some examples of learning activities: |

| |

| Inside school: |

|

|

Class teacher periods |

|

A talk at school assembly |

|

Ethics and religious education talks |

|

Participation in student organisations (such as flag-raising team, uniformed group (e.g. the Scouts), student union, and classroom/ school environmental protection activities) |

|

A thematic programme (such as serving others, debates or plays relevant to life events) |

|

A national education programme/ course |

|

A service learning programme |

|

The school as a family programme |

| |

| Outside school: |

|

|

Exchange and interflow educational programmes with the Mainland |

|

The Student Environmental Protection Ambassador Scheme |

|

The National Day Extravaganza |

|

A leadership training programme |

|

A community volunteer scheme |

|

A beach cleaning activity |

|

A visit (such as to Wetland Park, the Mai Po Nature Reserve) |

|

An experience workshop on social integration |

|

The regional civic education programme |

|

A field study of the community |

| |

| Aesthetic Development |

| |

| Besides fostering students' life-long interest in the arts and cultivating positive values and attitudes, Aesthetic Development plays an important role in helping students to lead a healthy life and achieve whole-person development. As no public examinations are required for Aesthetic Development, students can learn the arts in a more relaxing way through appreciating, creating, performing and reflecting. Aesthetic Development is different from the elective subjects of Music and Visual Arts. It aims to provide all senior secondary students with rich and meaningful arts learning experiences, while Music and Visual Arts aim to help individual students to develop their specialisation in these two arts areas. |

| |

Example: An Arts Programme that Builds on Existing Strengths |

| |

| School Q has a tradition of offering General Music to SS Students. To implement Aesthetic Development in OLE, the school broadens student learning by providing all SS students with a double period lesson of Music or Visual Arts per cycle. Various arts groups and artists are invited to conduct different types of arts activities such as instrumental master classes, live dance performances and talks on film appreciation. The school also arranges students to visit exhibitions and stretches their talents through participating in external competitions related to the arts. |

|

|

| |

Example: Diverse Arts Learning Opportunities for Students |

| |

| School R allows all SS students to take part in learning modules of various art forms such as visual arts, music, dance, drama and media arts in the afternoon sessions. To consolidate their learning in the arts, students work collaboratively in groups to produce and present multi-media performances at the end of the school year. The school also encourages students to participate in arts-related community activities such as giving music and drama performances at hospitals and organising fund-raising exhibitions for the elderly. |

|

|

| |

| Suggested modes of implementation |

| |

|

Structured arts learning sessions:

The provision of structured arts learning sessions is an important mode of implementation for Aesthetic Development. For example, schools can offer music, visual arts, drama and/ or dance lessons in each cycle/ week, as well as organise structured arts learning days. |

|

A variety of co-curricular activities related to the arts:

To complement the learning in structured arts learning sessions, schools should arrange a variety of co-curricular activities to engage students in learning of arts in authentic contexts. For example, students can attend arts seminars and concerts, join guided tours on arts exhibitions, work with artists, as well as participate in community arts services and arts exhibitions, performances, competitions and training programmes. |

| |

| Please visit the website at http://www.edb.gov.hk/arts/aesthetic for more information on Aesthetic Development. |

| |

| Physical Development |

| |

| Physical Development develops students’ confidence and generic skills, especially those of collaboration, communication, creativity, critical thinking and aesthetic appreciation. These, together with the nurturing of positive values and attitudes, and perseverance in PE, provide a good foundation for students’ life-long and life-wide learning. |

| |

| Among the relevant values in the following, perseverance is to be highlighted in Physical Development through appropriate learning activities. |

| |

|

| |

| The provision of Physical Development in OLE should differ from that of PE as an elective subject, since the latter aims to enable students to address issues related to “body maintenance”, “self enhancement” and “community concern” in the context of physical education, sports and recreation, drawing on knowledge in physiology, nutrition, physics, sociology, psychology, history and management science. Hence, the PE Elective and the Physical Development element of OLE are interrelated, but with different emphases. |

| |

| Suggested modes of implementation: |

| |

|

|

PE lessons:

The recommended mode of implementation is PE lessons. They constitute a major part of the PD time allocation to help to ensure that students can enjoy a broad and balanced programme featuring a variety of movement experiences. Schools should note that only teachers with proper training in the teaching of PE should be assigned to teach PE lessons. |

|

A variety of physical development-related co-curricular activities:

Life-wide learning is important for student learning as it is not confined to lessons. Physical development-related co-curricular activities complement the learning in PE lessons, enrich student learning experiences, and widen their exposure to various physical activities. To this end, schools should encourage students to participate actively in interest groups or training courses of different physical activities, inter-school sports competitions or physical activities, whether inside or outside the school, or at their leisure. |

| |

| To ensure students’ safety during physical activities, schools should observe the recommendations set out in the “Safety Precautions in Physical Education for Hong Kong Schools”, the “Guidelines of Outdoor Activities” or other safety guidelines published by EDB. |

| |

| Community Service |

| |

| Community Service helps students to nurture respect for others and a caring mind, especially for disadvantaged members of society. Through Community Service, students develop civic responsibility towards the community via activities such as environmental conservation projects and Clean Hong Kong campaigns. |

| |

| Community Service in the SS curriculum should be built on prior experience in basic education. Schools should offer a range of opportunities with different levels of participation to cater for different needs and interests. In addition, schools should motivate students by offering them a variety of Community Service choices. Activities might range from service opportunities inside school and cleaning parks in the local neighbourhood to volunteer work in a social service agency; helping students or other stakeholders in their own schools and younger children in a local kindergarten, to serving in an elderly home. |

| |

| Community Service is both a means and an end in itself, serving a variety of learning aims or objectives. |

| |

|

| |

Example: The Story of V-Net |

| |

| In School T, volunteer service is seen as meeting two important ends – one, to serve the very young and the elderly; two, to provide valuable experiences for all students that build up their self-confidence, empathy and leadership. Service opportunities were not only offered to ‘keen students’, but also to students who were labelled as ‘disruptive’ and ‘uncontrollable’. The social worker who manages the V-Net was determined to provide a variety of tailor-made service opportunities, ranging from ‘taster’ experiences to advanced service programmes for enthusiasts. As a result of joining these programmes, many students changed their attitudes from ‘being disruptive’ to ‘being proactive’ in helping others. The V-Net manager also found that a previously ‘shy’ student became a confident and sensible leader among her peers, after joining V-Net. |

|

|

| |

| (Please refer to http://www.edb.gov.hk/cd/lwl/cs/ for more details.) |

| |

| Some examples of learning activities: |

| |

| Community service could be conducted in a wide range of contexts and purposes, both inside and outside school, such as, |

| |

|

service opportunities inside school, e.g. the student union, peer mentoring scheme, student librarians; |

|

service opportunities arranged by uniformed groups; |

|

participating in various community service activities organised by local community centres; |

|

organising events and activities for different social groups (including other schools) within the community; |

|

inviting target groups to schools for activities (e.g. a Chinese New Year variety show); |

|

Flag Days for charity organisations; |

|

a group of students organising a charity sale; |

|

Clean Hong Kong activities; |

|

helping younger children to learn English or plan an educational project, as mentors in a local primary school; |

|

environmental protection and neighbourhood improvement programmes; and |

|

serving as helpers in local libraries. |

| |

| Career-related Experiences |

| |

| Career-related Experiences (CRE) enable students to obtain up-to-date knowledge about the world of work. Work ethics, such as integrity, commitment and responsibility are emphasised in these activities, so that students have a good idea of what will be expected of them in their future working life. |

| |

| Schools are encouraged to organise suitable activities to achieve the above learning intentions, building on their existing career education policies (see Booklet 9). Schools may choose from a wide variety of formats and approaches to CRE, such as classroom activities, job attachments/ placements, job shadowing, career talks/ exhibitions, study visits to special workplaces and projects involving interviewing professionals/ experts. |

| |

| A quality CRE should address dimensions such as: |

|

Student perceptions on ‘the world of work’ - Profiling perceptual components of the world of work or the occupational fields concerned; |

|

Work ethics - the concept of good working attitudes (e.g. punctuality, team work spirit, integrity) related to the experience; |

|

Knowledge related to employability - Understanding of the current labour market and the notions of ‘employability’, with examples of possible entry points, progressions and trends in the selected field, as well as ‘personal qualities’ required, in the light of encouraging personal career planning and development; and |

|

Good use of community/ business partnerships and existing social networks (e.g. alumni, parents, within schools’ sponsoring bodies) is particularly useful for organising quality CRE to students. |

| |

|

| |

| (Please refer to http://www.edb.gov.hk/cd/lwl/cre/ for more details.) |

| |

Information on EDB’s Business-School Partnership Programme Website:

(http://www.edb.gov.hk/index.aspx?nodeid=4738&langno=1) |

| |

| Some examples of learning activities: |

|

| |

| |

| 5.7 Harnessing Community Resources |

| |

| Schools can harness a variety of community resources to strengthen their OLE programmes. Fostering good partnerships with local agencies is likely to be particularly beneficial. |

| |

| Many community groups are willing to support school functions and OLE by providing financial help, expertise, community facilities and appropriate learning experiences. Some organisations are also eager to offer ‘pre-packaged’ services specially designed for SS students so that teachers can concentrate on facilitating student learning in the process. In order to select appropriate community resources for student learning, schools should critically evaluate their probable effectiveness in accordance with the overall OLE aims and objectives. |

| |

Example: Community Service Programme by the HK Federation of Youth Groups |

| |

| Building on the success of helping P4-S3 students in a cluster of schools to engage in Community Service, the HK Federation of Youth Groups, which networks with a large number of social service agencies, launched a programme targeting at SS students. The overall aim was to nurture reflective and active citizenship among students through participating in Community Service. The programme also played an essential role in empowering teachers to be the facilitators in Community Service. |

Enquiry-based Programme

Becoming a reflective citizen |

Advocacy-based Programme

Becoming an active citizen |

|

Systematic enquiry into social issues encountered |

|

Apply appropriate actions to review and improve present social systems and values |

|

For SS students to |

|

Involving students and others |

| |

|

have some experiences in Community Service; and |

|

|

have a sense of civic responsibility; and |

| |

|

develop demonstrable ability to analyse and use critical thinking skills. |

|

|

develop organisation skills at a reasonable level. |

|

|

|

| |

| A databank specific to OLE that contains up-to-date activity information, useful contacts and websites has been launched to help teachers to draw on community resources and set up partnerships for OLE programmes. |

|

|

| |

| To promote a collaborative culture between schools and community partners, an interactive function is built into the website. Teachers are encouraged to provide feedback on their experiences with partners for others’ reference. |

| |

| |

Reflective Questions |

| |

|

Have there been any good practices in your school with regard to community partnerships for OLE? |

|

| |

|

How did you acquire up-to-date information on OLE-related community resources? |

|

| |

|

How did the co-ordinating team develop an understanding of the local community contexts, and how did the team build the capacity to select appropriate community resources as partners for OLE? |

|

| |

|

What have you learnt from these experiences? And how will this learning be helpful in future OLE programmes? |

|

|

| |

| |

| 5.8 Student Reflection as a Key to Success |

| |

| Reflecting on experiences can enhance learning. In order to learn effectively from experiences, students need sufficient time and support: |

| |

|

to connect with relevant prior experiences and make sense of it (e.g. “What is learned?”, “Why should I learn this?”); |

|

to extend their learning (e.g. “How could I learn more about this?”); and |

|

to challenge prior ‘knowledge’ (e.g. “I used to think…; Now I think…”) and learning pathway (e.g. “Why learning this way?”). |

| |

| The following factors are important to promote reflection amongst students in OLE: |

| |

|

Facilitating and leaving sufficient space for student reflection during and after the activity |

|

Developing a repertoire of pedagogical approaches (e.g. in briefing and de-briefing) to stimulate deeper thinking and to nurture reflective habits of mind among students |

|

Establishing a ‘reflection-conducive’ environment in school, based on trust, acceptance, and mutual respect of individual feelings, perceptions and beliefs. |

| |

| Reflection can be simply interpreted as enabling a person to ‘step back and think’ of an experience. In this sense, reflection is not necessarily in written form. In fact, such reflective thinking could be manifested or expressed in a wide range of forms in OLE contexts, such as journal or ‘blog’ writing, worksheets, tape recording own thoughts, talking with peers, power-point presentations, group discussions in de-briefing, drawing, designing a short play with a targeted audience or producing a promotional video collectively. |

| |

| |

Reflective Questions |

| |

|

How much time and support have you given for students to reflect deeply in OLE activities? |

|

| |

|

How can you improve student reflection? What strategies could work well so far? Are there any channels for sharing these strategies among colleagues in your schools? |

|

| |

|

How could you make student reflection more interesting and creative so that students would have better disposition towards it? |

|

|

| |

| |

| 5.9 Appraising Student Performance in Other Learning Experiences |

| |

| The ‘assessment’ of student performance in OLE should be designed to facilitate further learning and development. To enable teachers and students to value the process and plan for future engagement in OLE, a range of formative assessment modes such as self-assessment, peer-assessment, and portfolio assessment have been adopted in schools of diverse backgrounds. As observed in these schools, informal feedback has been effectively used to help students to learn how to learn and to participate better in various OLE activities. Schools are thus encouraged to build on their existing practices and adopt an appropriate ‘vehicle’ to enable further learning and to promote whole-person development. After all, the heart of OLE should be on Assessment for Learning, not formal summative testing. |

| |

| For this, every student is encouraged to build a Student Learning Profile through which tracking and reflecting on whole-person development could be possible during the period in the SS education. Schools could make good use of the profile to motivate OLE participation and reflection if appropriate. More elaboration can be found in Booklet 5B. |

| |

| |

Reflective Questions |

| |

|

Has your school arranged adequate and balanced OLE opportunities for all SS students? If yes, how? If not, why? |

|

| |

|

Building on existing strengths, what would be the short-term and medium-term targets of OLE in your school to promote whole-person and balanced development? |

|

| |

|

How will your school foster the kind of culture that is conducive to promoting quality OLE in the long run? |

|

| |

|

What would be the strategies adopted by your school to cultivate a culture of reflection among students over their OLE and personal development? |

|

| |

|

Has your school developed partnerships with parents, government departments, NGOs, etc? How does your school plan to do so in the future, and who will be involved? |

|

|

| |

| |

| Appendix I |

| |

|

|

|

| |

| Appendix II |

|

| |

| Some Suggested Expected Outcomes of the Five Areas of OLE |

| |

| Teachers may make reference to the following suggested expected outcomes of each area of OLE when planning their school-based OLE. |

| |

| Moral and Civic Education |

| |

| Through Moral and Civic Education, we expect our students to: |

|

develop and exemplify positive values and attitudes when dealing with personal and social issues pertinent to the development of adulthood; |

|

identify the moral and civic values embedded in personal and social dilemmas, and make rational judgements and take proper actions with reference to their personal principles as well as social norms; and |

|

become ‘informed’, ‘sensible’ and ‘responsible’ citizens who will care for others, develop a sense of identity and commitment to society and the nation, and show concern for world issues. |

| |

| Aesthetic Development |

| |

| Aesthetic Development in OLE is expected to help students to further: |

| |

|

develop their creativity, aesthetic sensitivity and arts-appraising ability; |

|

cultivate their respect for different values and cultures; and |

|

cultivate their life-long interest in the arts. |

| |

| Physical Development |

| |

| Through Physical Development in OLE, students should be able to: |

| |

|

cultivate core values, such as perseverance, responsibility, commitment and respect for others; |

|

refine the skills learnt and acquire skills of novel physical activities, and participate actively and regularly in at least one PE-related co-curricular activity; |

|

analyse physical movement and evaluate the effectiveness of a health-related fitness programme; and |

|

take the role of sports leader or junior coach in school and the community, and demonstrate responsibility and leadership. |

| |

| Community Service |

| |

| Through Community Service in OLE, we expect our students to: |

| |

|

identify and reflect on various social issues / concerns encountered in Community Service experiences; |

|

develop positive attitudes (e.g. respect and caring for others, social responsibility) and related generic skills (e.g. collaboration) to prepare for future voluntary service involvement; and |

|

nurture life-long interest and habits in Community Service. |

| |

| Career-related Experiences |

| |

| Through Career-related Experiences in OLE, we expect our students to: |

| |

|

enhance up-to-date knowledge about ‘the world of work’; |

|

acquire knowledge related to employability, in order to encourage personal career planning and development; and |

|

reflect on work ethics, and employers’ expectations in the current labour market. |

| |

| Other Information and Learning/ Teaching Resources: |

| |

| For OLE and SLP in general: |

|

|

| |

|

OLE Website (http://www.edb.gov.hk/cd/ole) includes an OLE activity databank, essential information on OLE/ SLP, good practices, conceptual frameworks, seed project information, tools and examples of SLP. A databank on OLE time arrangement illustrating different school practices has also been uploaded recently. |

| |

|

An SLP Module of WebSAMS has been launched in early 2008 for school reference or use if appropriate. For details, please refer to (http://www.edb.gov.hk/cd/slp). |

| |

|

For parent education, schools can refer to “Other Learning Experiences: A Journey towards Whole-Person Development” (Parent Education Resource) DVD (http://www.edb.gov.hk/cd/OLE/ole_dvd/). |

| |

|

Articles related to OLE are listed as follows: |

| |

|

Other Learning Experiences: A Catalyst for Whole-person Development |

| |

|

Eight Misconceptions about “Other Learning Experiences” and “Student Learning Profile” |

| |

|

A Self-checking Workflow of OLE Time Arrangement |

| |

|

The Role of “Community Service” in the SS curriculum: Kindle the Life of Serving Others |

| |

|

|

| |

For details, please refer to (http://www.edb.gov.hk/cd/ole/ole_articles/). |

| |

|

Guidelines to ensure student safety during activities: |

| |

|

Guidelines on Extra-curricular Activities in Schools |

| |

|

Guidelines on Outdoor Activities |

| |

|

Guidelines on Study Tour Outside HKSAR; |

| |

|

School Outings in Rural Areas: Safety Precautions; and |

| |

|

Government's advice for the public on seasonal influenza, avian influenza and influenza pandemic |

| |

| For details, please refer to (http://www.edb.gov.hk/index.aspx?langno=1&nodeid=3126) |

| |

| For individual components of OLE: |

|

Moral and Civic Education: |

| |

|

The Moral and Civic Education website (http://www.edb.gov.hk/cd/mce) provides the conceptual framework and curriculum information, as well as learning and teaching resources on various cross-curricular themes etc; |

| |

|

|

| |

|

Service Learning (http://www.edb.gov.hk/cd/mce/servicelearning/) |

| |

|

Community Service (http://www.edb.gov.hk/cd/lwl/cs/) |

| |

|

Career-related Experiences (http://www.edb.gov.hk/cd/lwl/cre/) |

| |

|

“Finding Your Colours of Life: NSS Subject Choices and the Development of Career Aspirations” jointly developed by the HK Association of Careers Masters and Guidance Masters and CDI.

(http://cd1.edb.hkedcity.net/cd/lwl/ole/ole_articles.asp) |

| |

|

Aesthetic Development (http://www.edb.gov.hk/arts/aesthetic) |

| |

|

The Aesthetic Development website provides suggested modes of implementation, examples of learning and teaching activities, information about Professional Development Programmes and community resources etc. |

| |

|

Physical Development: (http://www.edb.gov.hk/cd/pe/). |

| |

| |

| References |

| |

| Alt, M. (1997). How effective an education tool is student community service? NASSP Bulletin 81, n. 591, 8 – 17. US: SAGE. |

| |

| Beard, C. and Wilson, J. (2002). The Power of Experiential Learning. London: Kogan Page. |

| |

| Bentley, T. (1998). Learning beyond the classroom: education for a changing world. London: Routledge. |

| |

| Brandell, M. and Hinck, S. (1997).Service learning: connecting citizenship with the classroom. NASSP Bulletin 81, n.591, 49 - 56. US: SAGE. |

| |

| Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1993). The Evolving Self: a Psychology for the Third Millennium. New York: Harpercollins. |

| |

| Cumming, J. and Carbine, B. (1997). Reforming Schools through Workplace Learning. New South Wales: National Schools Network. |

| |

| Department for Education and Employment. (1998). Extending Opportunity: a National Framework for Study Support. London: Department for Education and Employment (DfEE). |

| |

| Eisner, E. (1979). The Educational Imagination: On the Design and Evaluation of School Programs. New Jersey: Merrill Prentice Hall. |

| |

| Foskett & Hemsley-Brown. (2001). Choosing Futures – Young People’s Decision - Making in Education, Training and Career Markets. London: Routledge. |

| |

| Hargreaves, D. (1994). The Mosaic of Learning: Schools and Teachers for the Next Century. London: DEMOS. |

| |

| IBO. (2001). Creativity, Action, Service Guide (English). Switzerland: International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme – for candidates graduating in 2003 and thereafter. |

| |

| Leung, Y. W. (2003). Citizenship Education through Service Learning: From Charity to Social Justice. Education Journal (教育學報), Vol. 31, No. 1, Summer 2003. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong. |

| |

| MacBeath, J. et al. (2001). The impact of study support: a study into the effects of participation in out-of-school-hours learning on the academic attainment, attitudes and attendance of secondary school students. UK: Department for Education and Employment (DfEE). |

| |

| Noam, G. (Ed.) (2004). After-school Worlds: Creating a New Social Space for Development and Learning. New Directions for Youth Development. No. 101. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. |

| |

| Stoll, L., Fink, D. and Earl, L. (2003). It’s About Learning (And It’s About Time): What’s in it for Schools? London: Routledge. |

| |

| Watkins, C. (2003). Learning: a sense-makers guide. London: Association of Teachers and Lecturers (ATL). |

| |

| 李臣之 (2000) 《活動課程的再認識:問題、實質與目標》,深圳:深圳大學師範學院。 |

| |

| 李坤崇 (2001) 《綜合活動學習領域教材教法》,台北:心理出版社。 |

| |

| 林勝義 (2001) 《服務學習指導手冊》,台北:行政院青年輔導委員會。 |

| |

| 高彥鳴 (2005) 《與青年人談全人教育》,香港:香港城市大學出版社。 |

| |

| 教育局 (2007) 《「其他學習經歷」 - 指南針》,香港:課程發展處全方位學習及圖書館組。 |

| |

| 鄧淑英、梁裕宏、黃嘉儀、李潔卿 (2008) 《創路達人の從零開始》,香港:突破出版社。 |

| |

|