Other Learning Experiences is one of the three major components of the Senior Secondary curriculum that complements the core and elective subjects (including Applied Learning courses and other languages) for the whole-person development of students. These experiences include Moral and Civic education, Community Service, Career-related Experiences, Aesthetic Development and Physical Development.

It is a way of organising the school curriculum around fundamental concepts of major knowledge domains. It aims at providing a broad, balanced and coherent curriculum for all students through engaging them in a variety of essential learning experiences. The Hong Kong curriculum has eight KLAs, namely, Chinese Language Education, English Language Education, Mathematics Education, Personal, Social and Humanities Education, Science Education, Technology Education, Arts Education and Physical Education.

Values constitute the foundation of the attitudes and beliefs that influence one’s behaviour and way of life. They help to form the principles underlying human conduct and critical judgement, and are qualities that learners should develop. Some examples of values are rights and responsibilities, commitment, honesty and national identity. Closely associated with values are attitudes. The latter supports motivation and cognitive functioning, and affects one’s way of reacting to events or situations. Since both values and attitudes significantly affect the way a student learns, they form an important part of the school curriculum.

Generic skills are skills, abilities and attributes which are fundamental in helping students to acquire, construct and apply knowledge. They are developed through the learning and teaching that takes place in different subjects or Key Learning Areas, and are transferable to different learning situations. Nine types of generic skills are identified in the Hong Kong school curriculum, i.e. collaboration skills, communication skills, creativity, critical thinking skills, information technology skills, numeracy skills, problem-solving skills, self-management skills and study skills.

Unlike direct instruction and construction approaches to learning and teaching, the co-construction approach emphasises the class as a community of learners who contribute collectively to the creation of knowledge and the building of criteria for judging such knowledge.

A learning community refers to a group of people who have shared values and goals, and work closely together to generate knowledge and create new ways of learning through active participation, collaboration and reflection. Such a learning community may involve not only students and teachers, but also parents and other parties in the community.

| Booklet 3 |

Effective Learning and Teaching – Learning in the Dynamic World of Knowledge |

|

| |

| This is one of a series of 12 booklets in the Senior Secondary Curriculum Guide. Its contents are as follows: |

Contents |

| 3.1 |

Purpose of the Booklet |

| 3.2 |

From Curriculum to Pedagogy – Key Challenges in Learning and Teaching the Senior Secondary Curriculum |

| 3.3 |

Wide Repertoire of Pedagogical Approaches: Matching with Different Learning Targets/ Objectives/ Expected Outcomes |

| 3.4 |

Effective Learning and Teaching Strategies |

| 3.5 |

The Quality Classroom: Major Highlights |

| 3.6 |

Values Education across the Curriculum |

| References |

|

| |

| 3.1 Purpose of the Booklet |

| |

|

To reiterate the key points of effective learning and teaching suggested in the Basic Education Curriculum Guide - Building on Strengths (CDC, 2002) |

|

To extend the meaning of effective learning and teaching in the context of senior secondary (SS) education |

|

To illustrate essential concepts with desirable practices and examples |

| |

| |

| 3.2 From Curriculum to Pedagogy – Key Challenges in Learning and Teaching the Senior Secondary Curriculum |

| |

| The key challenge for teachers is to put the curriculum aims with regard to content knowledge, generic skills and values into everyday classroom practice to enable students to apply what they have learnt in new and unfamiliar contexts effectively. This implies the development of teachers’ professional strengths in the design of learning and teaching strategies and application of a wide range of effective learning experiences, including in particular those that lead to in-depth understanding, enquiry and problem-based learning, and those that engage students in collaborative learning both inside and outside school. |

| |

| To realise the rationale underlying the New Academic Structure reform in the classroom context, teachers need to |

| |

|

have a wide repertoire of pedagogical strategies to cater for different learning intentions, individual students’ needs and learning environments; |

|

apply a pedagogy, old or new, that engages students, supports them to develop thinking and problem-solving skills and enables them to develop life-long learning skills; and |

|

align assessment practice with curriculum change and recognise the wider achievements and abilities of students.

|

| |

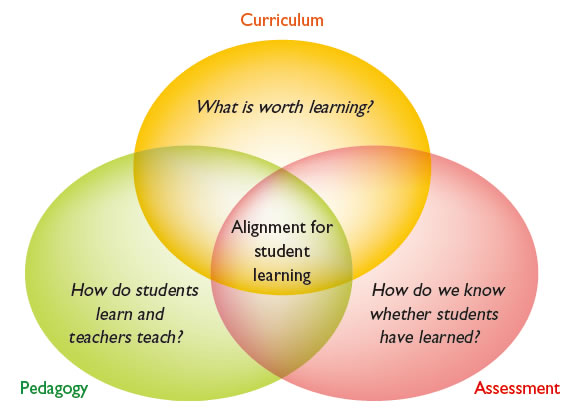

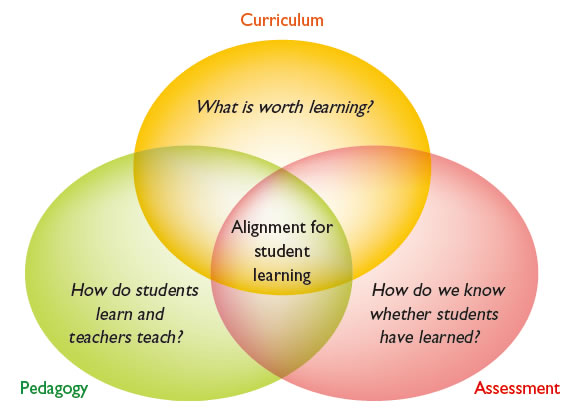

| It is worth reiterating that the three key elements of student learning, i.e. Curriculum, Assessment and Pedagogy, should interlock and align (see Figure 3.1). Sometimes teachers focus too much on curriculum and assessment and neglect the importance of pedagogy in implementing a new subject curriculum. Realising curriculum goals through effective classroom pedagogies is of crucial importance too. In order to understand more about what kind of pedagogy is needed, it is helpful to consider current views of learning and teaching in section 3.3. |

| |

Figure 3.1 Interlocking relationship among Curriculum, Pedagogy and Assessment |

|

| |

| |

| 3.3 Wide Repertoire of Pedagogical Approaches: Matching with Different Learning Targets/ Objectives/ Expected Outcomes |

| |

| The most important principle for choosing suitable pedagogical strategies is ‘fitness for purpose’. There is no single pedagogical approach that can fit all requirements. In fact, teachers need a wide repertoire of learning and teaching strategies to suit the varying contents, aims and focuses of learning. |

| |

| Learning and teaching strategies can be divided into three categories, in accordance with the following three views of learning and teaching. |

| |

| Teaching as ‘Direct Instruction’; learning as a ‘Product’ |

| |

| This view gives rise to a wide range of activities based on the notion that learning involves the transmission of knowledge from teacher to learner. From the students’ perspective, these activities include being told, being lectured at as well as reading and learning by heart from textbooks/ reference books. Teachers should not eliminate direct instruction as a teaching approach for the following reasons: |

| |

|

This approach may be most relevant when the objectives are to teach explicit procedures or facts. |

|

Teachers often employ such an approach when they need to convey a number of ideas in which students have little background. |

|

Other learning strategies such as an enquiry-based approach may not be well suited to conveying information, especially if the students have little background knowledge. |

| |

|

| |

| Teaching as ‘Enquiry’; learning as a ‘Process’ |

| |

| This view includes a range of strategies that are often used in more complex cognitive processes requiring meaning-making. The focus is often on the learners’ understanding and concept development. Students are encouraged to help each other to raise questions and show understanding.

|

| |

| Such enquiry-based learning can involve interactive whole-class teaching or interactions in pairs or groups and may also involve: |

| |

|

eliciting prior understanding and experiences; |

|

placing a topic in a wider and meaningful context; |

|

resource-based learning techniques (e.g. selecting appropriate information for learning); |

|

issue-based or problem-based learning strategies; |

|

group work to investigate an issue; |

|

using open-ended questions; |

|

reflecting and discussing among peers with suitable ‘wait time’; |

|

encouraging explanations or elaboration of answers; and |

|

quality de-briefing. |

| |

| It is generally agreed that finding out what is in the learners’ minds and identifying learner needs should be the key strategies for improving the quality of student learning in the classroom. The following is a list of practical strategies which encourage quality discussions in pairs, larger groups or the whole class: |

| |

|

Leave more ‘wait time’ after asking a question |

|

Instead of correcting a wrong answer, tease out a better one by taking the question round the class or explore the ‘wrong’ answer to find out how the student is thinking |

|

Change the ‘hands up to answer’ rule on occasions to ‘no hands up unless asking a question’ |

|

Encourage students to ‘think, pair and share’ regularly during the lessons, i.e. to think about an answer initially as an individual, then join with a partner to share ideas, then pair up again with another pair and repeat the process with the larger group |

|

Use posters and leaflets to promote good practices of making classroom more interactive among teachers and students |

|

Focus more on dialogue and less on writing. |

| |

| Learning and teaching as ‘Co-construction’ |

| |

| This view embraces approaches that put more emphasis on building knowledge in a ‘community’, mirroring the research communities and adult learning within professional fields. Co-construction of knowledge involves the teacher and the students in interaction. The teacher is as much a learner as the students in this approach. |

| |

| A variety of links are made between members of the class and with other sources of knowledge in the world outside the classroom. The power relationship in the classroom is unusual in the sense that teachers and students are of ‘equal status’ and both contribute to the general building up of knowledge. |

| |

| Appropriate ‘scaffolding’ or tools are used to facilitate such learning, for example: |

| |

|

using an electronic tool to build a ‘knowledge forum’ to provide a learning platform on a topic of interest to students, teachers and external experts; and |

|

using other ‘scaffolds’ to assist co-construction, including rehearsing arguments with peers and using self-evaluation checklists. |

| |

Example: Building a Learning Community among Students and Teachers |

| |

| A group of teachers decided to introduce some practical strategies to nurture learning communities at their senior student level across several subjects (e.g. Liberal Studies, humanities). Three main facilitating strands were identified: |

|

The need to build a sense of community and membership |

|

The need for more team work and network communications for learning |

|

The need to encourage teachers and students to take responsibility for learning together. |

| |

|

| In order to build a sense of community and membership, teachers employed the following ‘ABCD’ principles in their normal lesson planning: |

|

Adopted active arrangements for teachers and students to work together |

|

‘Bridged’ with each other (i.e. teachers and students) in learning activities |

|

Collaborated (i.e. in the co-construction of new knowledge) |

|

Diversity (engaged in dialogue with one another, relating to each other as critical friends). |

| |

|

| Teachers recognised that the main task was to encourage the students to see themselves as members of a common learning community, to take up the responsibility of co-construction, and to see each other as partners in learning. The learning experience was found to be useful for SS students in helping them to understand how knowledge is built in wider communities (e.g. in universities, among professionals). The approach was found to be universal to all subjects but particularly useful in Liberal Studies and in some topics of humanities and science subjects. |

|

|

| |

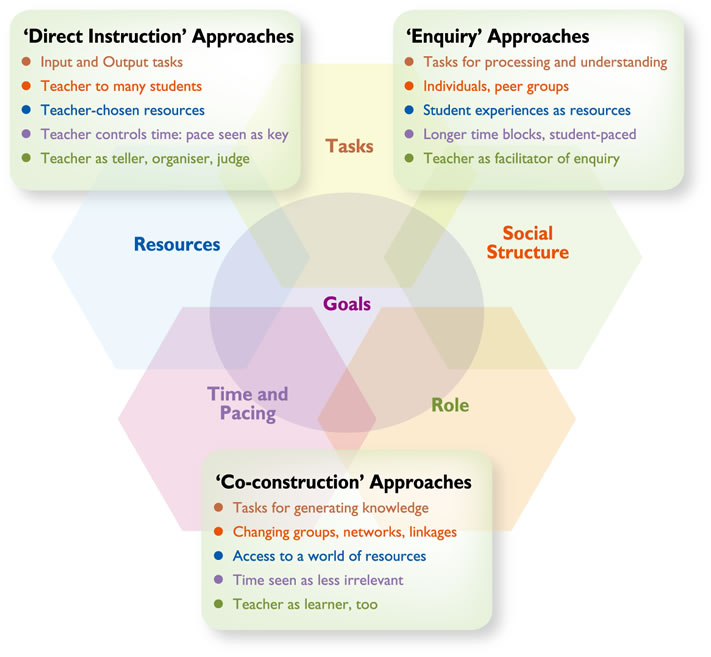

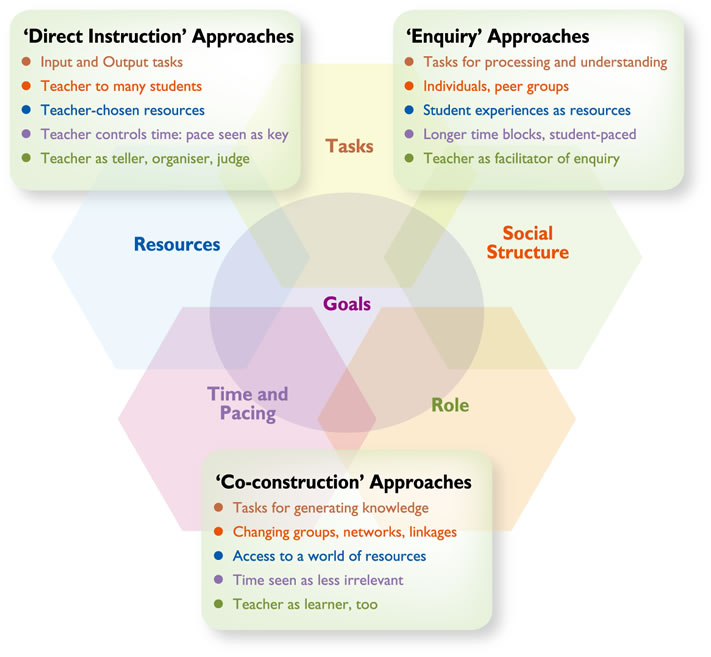

| Watkins (2005) summarises how the approaches among the three main views of learning and teaching differ from each other, in terms of classroom activity systems: Tasks, Social Structure, Resources, Roles, Time and Pacing. |

| |

Figure 3.2 Classroom Activity Systems across the Three Main Views of Learning and Teaching |

|

| |

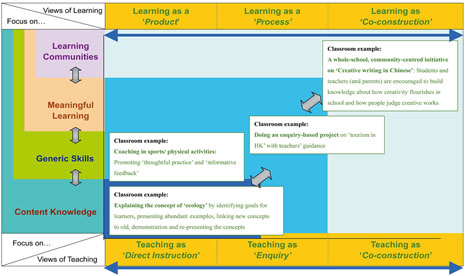

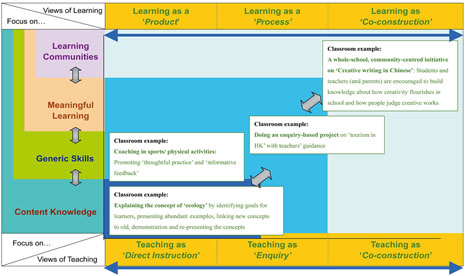

| Figure 3.3 presents a summary diagram of learning and teaching approaches that could be adopted in the SS curriculum. In the horizontal dimension, it shows a spectrum of different pedagogical views and approaches available for choices to suit different purposes. On the vertical axis, it highlights a range of learning focuses and purposes (i.e. from content-centred to learning community-centred) that teachers may build upon in their daily teaching practices and which corresponds to certain kinds of pedagogical views on the horizontal axis. Classroom examples are then briefly mapped in the chart for illustration. |

| |

Figure 3.3 Learning and Teaching Strategies and Approaches |

(click to enlarge view)

|

| |

| Teachers can identify their current practices and any gaps that they might want to fill to build up their repertoire through professional development (See case example below). |

| |

Example: Widening the Pedagogical Repertoire; Developing Professional Strengths |

| |

| Teacher A has been teaching science for twelve years. In order to teach many scientific concepts, she chooses to use a wide range of direct instruction strategies as her main pedagogy. Occasionally, she also uses ‘enquiry’ methods to help students to engage in scientific investigations in the SS curriculum. In order to enrich her existing pedagogical repertoire, she decides to try out some ‘co-construction’ ideas on topics such as ‘the social impact of nuclear power’, first in the context of the school’s Science Club and then with the top group of students, using a web-based knowledge forum. She re-structures the SS programme and builds in some relevant ‘co-construction’ activities, e.g. debates, discussion forums and project work to nurture a ‘learning community’ culture. |

|

|

| |

| |

Reflective Questions |

| |

|

How do your students normally learn? What strategies do they use most easily? What are the strengths of different students? |

|

| |

|

How would you match the strengths of your students in learning with your strengths in teaching to achieve the short-term targets of the curriculum of the subject? What practices need to be modified? |

|

| |

|

What gaps do you see in your own pedagogical practices? Which of the approaches above would you like to adopt in order to learn further? |

|

|

| |

| |

| 3.4 Effective Learning and Teaching Strategies |

| |

| Professional teachers not only have a deep knowledge of pedagogy; they are also able to apply what they know to the diversity they find in their classrooms. This includes being able to use effective strategies and teaching techniques that they have developed through their own experience. |

| |

Some Examples of Learning and Teaching Strategies: |

| (a) An example of ‘Good’ direct explanation |

| After a series of school-based professional development sessions on pedagogy, the panel heads of school A gathered a few ‘self-check’ points to help junior teachers or ‘newcomers’ to refine their teaching practices in explaining ‘things’ to students. They concluded: |

1. |

good explanation is a matter of providing clear information (with appropriate choice of presentational tools); |

2. |

good explanation provides the backgrounds and contexts of the matter or concepts; |

3. |

good explanation includes information about not only the ‘what’ but also the ‘how’ (e.g. ‘How could I apply the technique or concept?’) and the ‘when’ of the matter (e.g. ‘When could I use the concept or fact?’); and |

4. |

good explanation involves monitoring students’ evolving understanding and their points of confusion and uncertainty in order to clarify these. |

| |

| (b) An example of ‘Multi-perspective Thinking’ |

| In order to promote deep multi-perspective thinking in a Moral & Civic Education lesson, |

1. |

Teacher B presents a controversial real-life story to students and asks them to write their personal views about the case. |

2. |

Students are asked to discuss the moral issues behind the story in groups, role-playing as one of the characters (X, Y, Z) or as parties (e.g. the government, pressure groups, …). |

3. |

Students are asked to exchange the role-playing character/ party and groups are encouraged to report back to the whole class. |

4. |

At the end of the exercise, individual students are asked to reflect on different perspectives and to identify any changes of personal views. |

| |

|

| (c) An example of ‘Experiential Learning’ or situated learning |

| Coupled with structured briefing and de-briefing, this strategy could be used in many contexts in the SS curriculum, e.g |

1. |

Students can learn writing skills by publishing a newsletter for fellow students or parents. |

2. |

Students can learn about statistics by engaging in research relevant to their immediate surroundings; for instance, statistics on the school sport teams. |

3. |

Business students can be encouraged to run a virtual or small business with support from a business mentor. |

| |

| (d) An example of ‘Jigsaw’ team work strategies |

| Instead of directly explaining a topic, which comprises 4 sub-topics (X,Y, Z and W), teacher C chooses a ‘jigsaw’ team work technique to allow students to work through the related concepts in a very active way. |

1. |

Students form groups of five and divide a given topic into sub-topics, each student in a group taking responsibility for teaching the others one sub-topic. |

2. |

The students responsible for X leave their small groups and form a larger group that learns about X from the next group, the teacher, and other resources. They do likewise for Y, Z and W. |

3. |

Then the students go back to their small groups and teach one another their sub-topics. |

4. |

After testing, each student receives a grade to indicate the average performance of his or her group. Thus, each is motivated to see that all do well and to accept responsibility for team effort. |

|

|

| |

| It is worth reiterating that traditional learning and teaching strategies (e.g. didactic instruction) have their place and there is often more than one effective way of achieving a learning goal (see Booklet 7).

|

| |

| In using different strategies, teachers can assume different roles during the learning and teaching process, as transmitters of knowledge and as resource persons, facilitators, counsellors, and co-learners. |

| |

Roles of Teachers |

Actions (examples) |

| Transmitter |

Give lecture, provide information |

| Facilitator |

Discuss with students, provide guidance in the process |

| Resource person |

Advise on sources of information, provide an access to the world of resources outside the classroom, build networks for learning |

| Counsellor |

Provide advice on study methods and pathways |

| Assessor |

Inform students of their strengths, weaknesses and general progress and how to improve |

| Leader |

Take the lead in motivating student learning |

| Co-learner |

Learn alongside students |

|

| |

| Research shows that there are several noticeable school practices that are highly conducive to a better Learning to Learn school culture. Such a positive culture is generally associated with different practices at the following three levels, namely: |

| |

| At classroom level: |

|

Making learning explicit |

|

Promoting learning autonomy among students. |

| |

| At teachers’ professional learning level: |

|

Carrying out joint enquiries or evaluations with colleagues |

|

Building up social capital through learning, supporting and talking with one another |

|

Engaging in critical and responsive learning through reflection, self-evaluation, experimentation and responding to feedback |

|

Valuing both teachers’ professional learning and student learning. |

| |

| In the school’s management system: |

|

Involving staff in decision-making and using their professional knowledge in the formulation and evaluation of school policy |

|

Developing a sense of direction on learning-related priorities through clear communication with senior staff |

|

Supporting professional development through a range of formal and informal training opportunities |

|

Auditing expertise and supporting networking within a school and among schools. |

| |

| 3.5 The Quality Classroom: Major Highlights |

| |

| The following sections will focus on what constitutes a quality classroom. Several aspects are of particular relevance to SS education, and are outlined below: |

|

|

Quality interaction in the classroom |

|

The classrooms as learning communities |

|

Other key features of a Quality Classroom, e.g. effective use of information technology (IT) and catering for learner differences. |

| |

| Quality interaction in the classroom |

| |

| Classroom ‘talk’ or interaction among students and teachers is a crucial pedagogical feature of every style of learning and teaching. In particular, a well-facilitated dialogue, as a more structured type of interaction supporting the exchange of ideas, understanding or opinions, helps students to make meaning through the interactive process. |

| |

| To help students in areas where learning is difficult, teachers can: |

|

break down the difficulties into manageable tasks; |

|

give helpful directions and point out useful means; and |

|

pose open-ended, guiding questions and provide feedback. |

| |

|

| Teacher support should be gradually reduced as the learners’ competence increases. Students need to learn how to interact with other learners and the teacher in more structured discussion designed to bring about the construction of knowledge, rather than always resort to the teacher for an authoritative answer. |

| |

|

| |

| Notes: |

|

Informative feedback from teachers is an important feature of quality interaction in the classroom. In recent research literature, teachers’ feedback ranks top in terms of the effect it has on improving learning outcomes. |

|

Providing informative feedback means helping students to correct a mistake, by taking them through their thinking, rather than correcting it for them. e.g. “Show me how you got that answer” rather than “No, the correct answer is ….”. |

|

Teachers can use feedback to: |

| |

|

clarify goals; |

| |

|

provide suitable suggestions; |

| |

|

give a sense of direction and purpose; |

| |

|

stimulate further learning; |

| |

|

open another dialogue or train of thought; and |

| |

|

provide advice for improvement. |

|

Teachers should avoid feedback and remarks which: |

| |

|

concentrate on marks; and |

| |

|

always focus on the person (e.g. “Well done, good girl”), instead of commenting on the person’s effort and work. |

| |

| |

Reflective Questions |

| |

|

What form of feedback has worked best for you? Why? |

|

| |

|

When and how should the above be employed in the teaching of your school in the future? What constraints need to be overcome? |

|

|

|

| |

| The classrooms as learning communities |

| |

| Classrooms in which students and teachers learn together can be called learning communities. In a learning community, everyone contributes in different ways to knowledge building. |

| |

| There are three main strands of development for building a learning community in a classroom: |

|

Building a sense of community (e.g. active participation, belonging, collaboration and dialogue) |

|

Instilling a commitment to learning (i.e. agreeing to a common learning agenda) |

|

Sharing responsibility for knowledge building. |

| |

| The key to success depends on the sense of membership within the community and how this membership is linked to the wider community. For example, in language subjects, it is important that the students see themselves as speakers of that language and are able to foster real-life links with communities speaking the language. |

| |

| Teachers should build on the existing strengths of building a collaborative culture in their classrooms. Research has shown that Hong Kong classrooms, under the influence of Asian cultures, are usually characterised by high levels of social support and students prefer a more collaborative environment for learning. |

| |

| |

Reflective Questions |

| |

|

What strategies will you use to build a learning community in your subject area? |

|

| |

|

Are there any tools and resources that you could draw on to more effectively help students to learn collaboratively? |

|

|

| |

| Other key features of a ‘Quality Classroom’ |

| |

| A classroom that encourages effective use of IT |

| |

| The unprecedented development in information and communication technology has provided a positive environment for learners. Student learning can be enhanced by computer simulations and modelling in addition to lively electronic presentations inside the classroom. The expanding Internet has also shaped many meaningful learning activities including a series of searching, comprehending, selecting, organising, synthesising, evaluating, reflecting and communicating activities. |

| |

| Teachers should seek appropriate opportunities to use IT to enhance their teaching. The Internet has provided a very effective means of facilitating interaction and supporting the building of a learning community among teachers and students. ;Communication and networking through e-mails, web-based instant messages, web journals (or ‘web logs’), etc. are common practices among the young, and teachers should make good use of such IT possibilities to build learning communities in school and in the wider world. However, the technology itself does not bring about learning, particularly when it is only used for its own sake. Learning is brought about through the way in which the technology is used to access information, share it, and apply it. |

| |

| A classroom that caters for learner differences |

| |

| Each student is unique, and the diversity amongst them found in a classroom encompasses learning abilities, learning styles, special needs, and interests/ motivations, etc.. |

| |

| Teachers should have reasonable expectations of their lower achieving students. Strategies like activity-based learning and multi-sensory learning1 can be effective in keeping weaker students engaged in learning. Sometimes, a modification of the curriculum plan is needed to cater for the less able to ensure that their self-confidence as learners is built up rather than destroyed. |

| |

| Students with higher ability need to have their learning capabilities stretched through extension work, independent assignments and the pursuit of personal interests. Learning objectives at various levels of challenge, and ability-based group work may help to differentiate learning tasks and allow mixed ability classroom learning and peer learning to take place (please refer to Booklet 7 for further details). |

| |

| In motivating students to engage in learning tasks, teachers also need to be aware that performance motivated by extrinsic rewards (e.g. grades, prizes) tends not to persist once the reward structure is dropped; whereas people are more likely to perform creatively and better in the long run if driven by strong intrinsic interest. |

| |

| 1Learning that involves the processing of stimuli through many sensory channels (e.g. through hearing, seeing as well as touching). The co-ordination of input from all the senses helps students (particularly the weaker students) to organise and retain their learning. |

| |

| A classroom that promotes understanding |

| |

| Effective classroom practice implies a focus on teaching for deep understanding, rather than for the mere memorising and recalling of facts. In topics that need memorisation, teachers need to bear in mind that memorisation does not mean ‘rote learning’ – i.e. learning without understanding. It is often found (especially in Asian culture contexts) that memorisation, when properly undertaken, can be useful as a foundation for promoting understanding, and vice versa. |

| |

| The challenge is to design a task that puts students to work, such as explaining something, solving a problem, building an argument, constructing a product, enabling them to demonstrate their knowledge and understanding and engage them in further learning. |

| |

|

| |

| |

| 3.6 Values Education across the Curriculum |

| |

| The promotion of values goes beyond knowledge construction and skills development. By means of the provision of interactive and reflective learning activities, instead of imposing values on students, the teaching and learning process should provide a sense of direction that enables students to |

| |

|

recognise the values inherent in the arguments and judgements; |

|

identify the values embedded in personal and social issues; |

|

be aware of their own values and attitudes in the choice of action; and |

|

develop positive values based on informed value judgements; |

| which exemplifies commendable, socially acceptable behaviour. |

| |

| Values promotion through the Key Learning Areas (KLAs) |

| |

| Different KLAs are important vehicles for nurturing values across the curriculum. To name a few, language subjects, humanities subjects and Liberal Studies offer a wealth of value-laden issues facilitating values development among students. Working within the context of knowledge and integrating learning with authentic scenarios of life; complemented with well-structured learning experiences (such as role-plays, discussions and debates on controversial issues), students are encouraged to listen to and accommodate diverse views, remove biases and re-prioritise choices. In so doing, students are helped to form their own value stance and beliefs. |

| |

| Values promotion through school ethos |

| |

| Values promotion is a longstanding process permeating through different learning contexts inside and outside the entire school environment. ;As action speaks louder than words, positive values development, e.g. caring, respect for others, hinges on role-modelling of related commendable behaviour by respective teachers and students, as well as on enhancing the school ethos, exemplifying similar good practices. |

| |

| Values promotion through Other Learning Experiences (OLE) |

| |

| Students should be provided with sufficient OLE opportunities (e.g. Community Service, Career-related Experiences) to cultivate positive values and attitudes. Such experiential learning (sometimes known as ‘learning-by-doing’) is essential in helping students to nurture sustainable personal development (see Booklet 5A for details). |

| |

| |

Reflective Questions |

| |

|

What personal/ departmental/ team/ whole school targets have you set in your school with regard to learning more about learning and teaching in the coming years? |

|

| |

|

What policies have you adopted to address issues such as catering for learner differences, the needs of gifted students and less able students, use of IT and OLE? How have these policies been communicated to teachers and students? |

|

| |

|

What is the overall school strategy relating to values education across the curriculum? In what way will the school further improve the promotion of values education through involving panels and KLAs? Apart from direct instruction, are there any learning strategies which could be highlighted to promote effective values education among subject teachers and teachers of Moral and Civic Education? |

|

|

| |

| |

| References |

| |

| Alexander, R. J. (2006). Education as dialogue: moral and pedagogical choices for a runaway world. Hong Kong: The Hong Kong Institute of Education in conjunction with Dialogos UK Ltd. |

| |

| Assessment Reform Group. (1999). Assessment for Learning: Beyond the Black Box. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Faculty of Education. |

| |

| Assessment Reform Group. (2002). Assessment for Learning: 10 Principles. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Faculty of Education. |

| |

| Black, P. and Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the Black Box: Raising Standards through Classroom Assessment. London: Kings College London School of Education. |

| |

| Black, P. et al. (2003). Assessment for Learning: Putting it into Practice. Maidenhead: Open University Press. |

| |

| Bransford, J. et al. (2000). How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience and School. Washington D.C.: National Research Council. |

| |

| Entwistle, N. (1988). Styles of Learning and Teaching: An Integrated Outline of Educational Psychology for Students, Teachers and Lecturers. London: David Fulton Publishers. |

| |

| James, M. et al. (2007). Improving Learning How to Learn: Classrooms, Schools and Networks. London: Routledge. |

| |

| Moseley, D. et al. (2003). Thinking Skill Frameworks for Post 16 Learners - An Evaluation Report to Learning Skills Development Council. U.K.: University of Newcastle Upon Tyne. |

| |

| Riding, R. & Rayner, S. (1998). Cognitive Styles and Learning Strategies: Understanding Style Differences in Learning and Behaviour. London: David Fulton. |

| |

| Swaffield, S. (2008). Unlocking Assessment. London: David Fulton. |

| |

| Watkins, C. (2003). Learning: a sense-makers guide. London: Association of Teachers and Lecturers (ATL). |

| |

| Watkins, C. (2005). Classrooms as Learning Communities: What’s in it for Schools? New York: Routledge. |

| |

| Watkins, D. & Biggs, J. (2001). Teaching Chinese Learners: Psychological and Pedagogical Perspectives. Hong Kong: Comparative Education Research Centre, The University of Hong Kong. |

| |

| Wood, D. (1998). How Children Think and Learn. Oxford: Blackwells. |

| |

|