Sharpening high-flyers’ writing and thinking skills in the assessment and feedback processes

Background

Assessment for learning (AfL) enables teachers to evaluate and improve the curriculum and teaching through students’ learning evidence, and helps students understand what is expected, what is being learnt, and what has been achieved (The Curriculum Development Council, 2017). In line with the school’s emphasis on AfL, English teachers of St. Clare’s Girls’ School used students’ scripts to identify their learning needs in writing and plan the follow-up support for students to enhance their writing performance. Students’ writing revealed two issues to be addressed: (1) logicality of an argument and (2) organisation of ideas in paragraph writing. In 2020/21, S4 English teachers deployed varied strategies to develop students’ higher-order thinking by enhancing their logical thinking and organisation skills for paragraph writing to boost their writing performance.

Level

S4

Strategies used

Using Bloom’s Taxonomy to guide the planning of the project

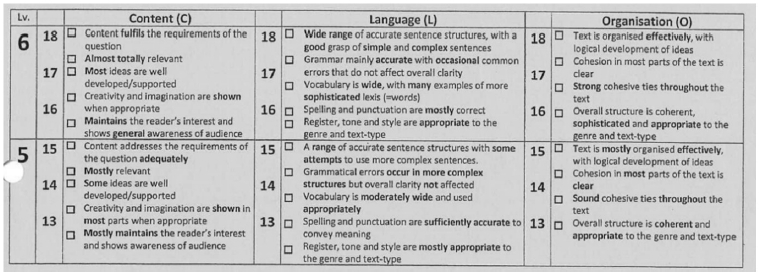

Bloom’s Taxonomy is commonly used for setting learning outcomes for assessment and instruction (Center for Learning Experimentation, Application, and Research, 2022). Learning tasks and activities of the project were designed according to the six levels of thinking skills, i.e. remembering, understanding, applying, analysing, evaluating and creating.

Figure 1 The latest version of Bloom’s Taxonomy

Source: Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching (released under a Creative Commons Attribution license)Adopting the PEEL framework in paragraph writing

No matter what topic students write, they need to present their ideas logically and coherently and give relevant details to support their ideas. They should also focus on one idea in a body paragraph and back up the point with evidence (Centre for Learning and Teaching, 2016). In view of these, the teachers introduced a strategy, PEEL (Point, Evidence, Elaboration/ Explanation and Link), to strengthen students’ body paragraph structure.Point:

Make a point (i.e. writing a topic sentence).

Evidence:

Support the point with evidence.

Elaboration/Explanation:

Explain how the evidence supports the point.

Link:

Link this point to the main point/the next point in the following paragraph.

Adapted from https://www.virtuallibrary.info/peel-paragraph-writing.html

Diversifying assessment and feedback practices to strengthen students’ thinking and writing skills

Assessment and feedback are essential to planning, learning, teaching and evaluation. In addition to using conventional pen-and-paper assessments, the teachers used a range of assessments such as debates and self-reflections to evaluate student learning and plan the follow-up support. Giving students formative feedback can enhance students’ knowledge, skills and understanding towards certain areas of content and general skills (Shute, 2007, as citied in Lam, 2013). Formative feedback can be in different forms (e.g. verbal feedback), and is usually given regularly during lessons (Lam, 2013). Through carefully-designed tasks and activities, S4 teachers provided opportunities for students to receive timely feedback in different forms (e.g. peer assessment, an online feedback session) to improve their students’ writing and thinking skills.

What happened

Designing tasks to stretch students’ cognitive skills

By making reference to Bloom’s Taxonomy, S4 English teachers designed tasks and activities to enhance student learning at all six levels. The table below shows examples of how some levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy were used at different stages:Levels

Stages

Examples

Remembering

Pre-writing

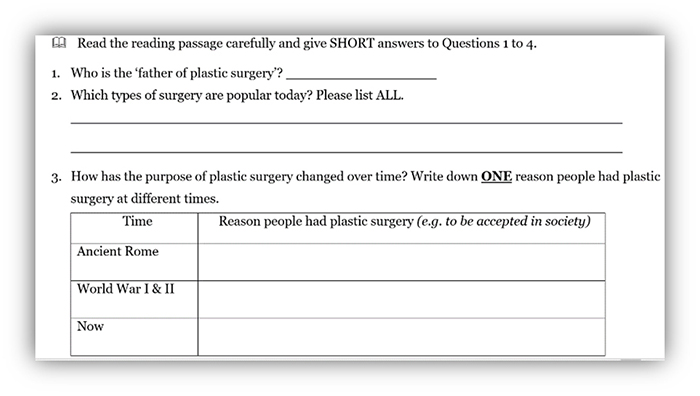

To help students understand the topic “plastic surgery” from multiple perspectives (e.g. historical development, a surgeon, teenagers), teachers provided them with reading texts and online videos, and designed some comprehension questions requiring students to answer by retrieving information from the materials, (see Picture 1).

Picture 1 Students being required to retrieve information from the materials to answer the questions

Understanding

Pre-writing

After doing two pre-tasks which helped them understand different stakeholders’ viewpoints on plastic surgery, students summarised the benefits and possible risks of plastic surgery to demonstrate their understanding of the topic (see Attachment 1).

Applying

Pre-, while- and post- writing

Students learnt how to write a rebuttal paragraph of a debate speech in a three-step approach:

1. Summarising the opposing ideas

2. Acknowledging the valid part

3. Refuting the opposing view by providing evidence (e.g. examples, facts, statistics)

Students then applied the above techniques in the pre-writing tasks, the writing task itself and an online writing conference.Analysing

Pre-writing

Based on the online videos and a reading text given in Pre-task 1 and Pre-task 2, students inferred different stakeholders’ attitudes towards plastic surgery in Pre-task 3 (see Attachment 1).

Evaluating

Pre-writing

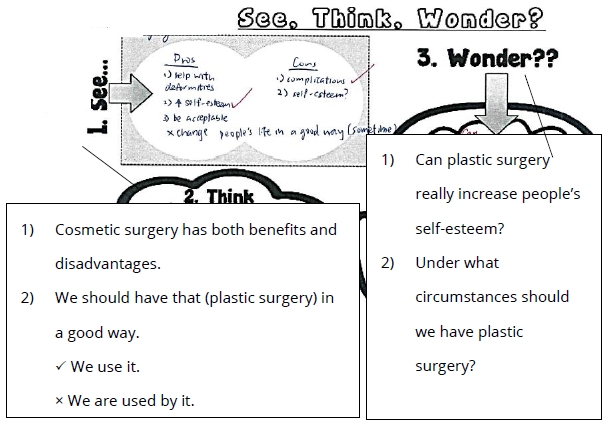

Students evaluated the surgeon and the psychologist’s ideas by using the “I see, I think, I wonder” approach to construct their own views on the topic (see “2. Think” in Picture 2). They could also formulate some questions to help them evaluate if plastic surgery was beneficial or harmful, encouraging them to find more evidence to support their views (See the two examples in “3. Wonder” in Picture 2).

Picture 2 A student using the “I see, I think, I wonder” approach to make her own judgement (edited and retyped)

Creating

While-writing

Students produced their own debate speech with the motion “all plastic surgery should be banned” by applying what they had learnt (e.g. rebuttal techniques, PEEL).

Using scaffolds to build up and reinforce students’ writing technique

To enhance students’ paragraph writing, teachers designed scaffolding activities to help them understand what PEEL is and how to use it. The scaffolding activities were designed with reference to Bloom’s Taxonomy:Levels

Activities

Remembering

Students learnt about basic concepts of PEEL through definitions and explicit teaching.

Understanding

Students identified the PEEL elements in a body paragraph of a sample writing through highlighting, underlining, bracketing and circling.

Applying and Creating

Students used PEEL to create a new body paragraph for the sample writing as a form of practice.

Designing varied assessment tasks to enhance student learning

Besides the writing task and the final examination, teachers designed other meaningful tasks and activities to strengthen students’ writing and thinking as well as sharpen their metacognitive skills.Tasks/Activities

Details

Post-writing tasks

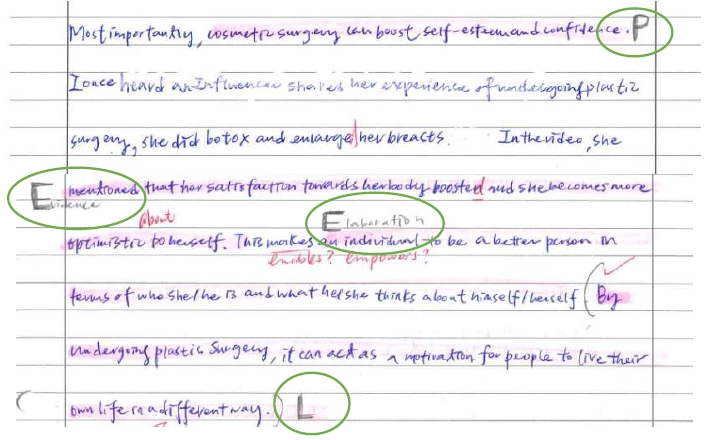

Students were asked to identify and label the four elements of PEEL in their peers’ writing for reinforcement (see Picture 3).

Picture 3 A student identifying and labelling the PEEL elements in peer’s writing (unedited work)

Teachers also designed post-writing tasks based on their own students’ areas for improvement. Students in an S4 class were asked to review and rewrite body paragraphs of their debate speech using PEEL. In another class, students were asked to identify the problems of the ideas given by their teacher and rewrite them where necessary.

Debates

An intra-class mini-debate was conducted during English lessons. Expectations such as maintaining eye contact and giving examples were clearly communicated to students. In the debate, students needed to transfer the knowledge and skills learnt (e.g. paragraph structure, development of arguments, rebuttal techniques) from writing to speaking. The activity also stretched their thinking skills by requiring them to find flaws in the opposing side’s arguments, and present their analyses and judgements by providing sound and valid evidence. Furthermore, students were asked to decide if the affirmative or negative team won the debate, which required them to evaluate each side’s performance as members of the audience.

Picture 4 Students transferring their knowledge and skills from writing to speaking

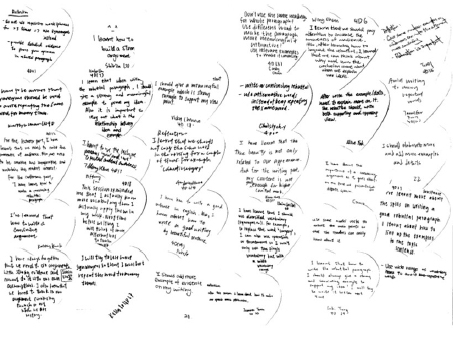

Self-reflection

After attending an online feedback session on the writing task, students wrote short reflections on post-it notes about their learning such as what they had learnt, what they once forgot but recalled through revisiting what had learnt (see Picture 5).

Picture 5 Students’self-reflections on their learning

Using rubrics to facilitate self-reflection and giving of constructive feedback

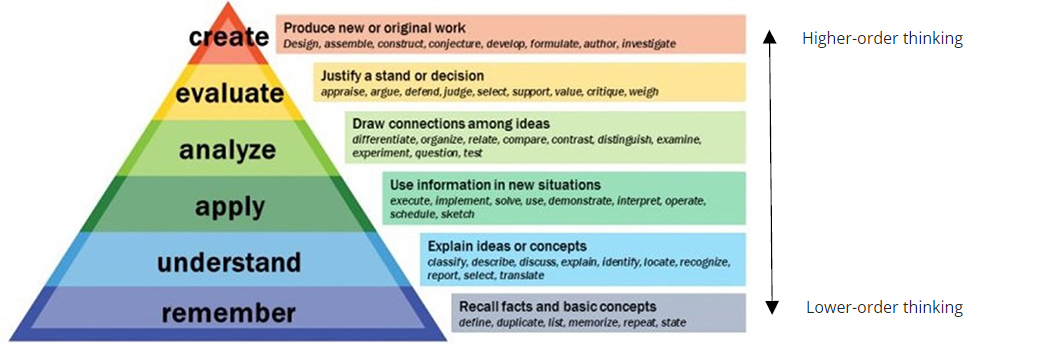

Clear assessment criteria for the debate and the writing task were set to enable students to reflect on their own performance in a more focused manner. Feedback from teachers and peers, with reference to the same set of criteria presented in the form of descriptors and checklists, helped students make targeted improvement.

Parties involved |

Forms of feedback |

Major tasks done |

Teachers |

Scores and descriptors |

In addition to giving scores on students’ writing, teachers used an analytic rubric to mark the debate speeches. Part of the rubric is shown in Picture 6. Teachers ticked the boxes next to descriptors that could best describe students’ writing. With the rubric, students could better understand their actual performance, encouraging them to set a higher goal and think about how to make improvement for the next writing task.

Picture 6 The rubric teachers used to mark students’debate speeches |

Written |

Specific comments on students’ writing in different areas (e.g. use of PEEL and rhetorical questions, relevance and development of ideas and audience awareness) were given. In the post-writing tasks where the paragraphs were reviewed and rewritten, students received teachers’ written feedback on, for example, the evidence and the tone. |

|

Oral |

Verbal feedback was given after each round of the intra-class debates. Students received comments on different aspects including the development of ideas, techniques used (e.g. rhetorical questions, examples and rebuttal), delivery and communication strategies (e.g. eye contact and voice), helping them improve their organising, thinking and speaking skills. |

|

Students |

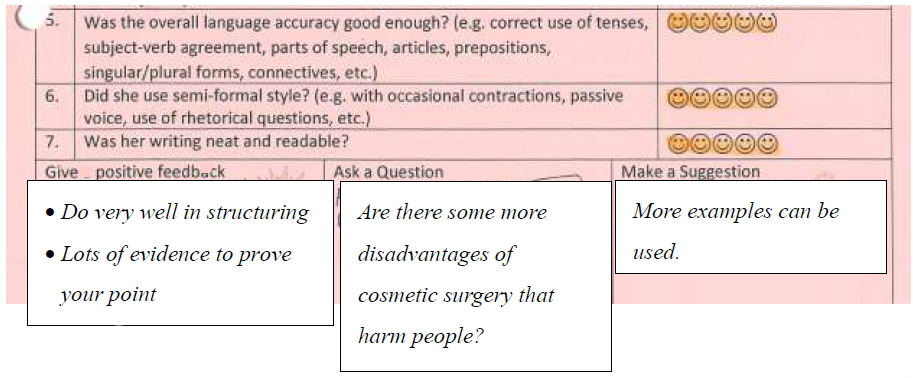

Checklist and written |

Peer assessment was conducted for students to review more critically their peers’ work. They were given a peer evaluation form (see Attachment 2) which aligned with what students learnt in the project to evaluate each other’s work against the task requirements. They were also asked to give written feedback on their classmates’ writing (see Picture 7).

Picture 7 A student’s written feedback given to her classmate (edited and retyped) |

Written |

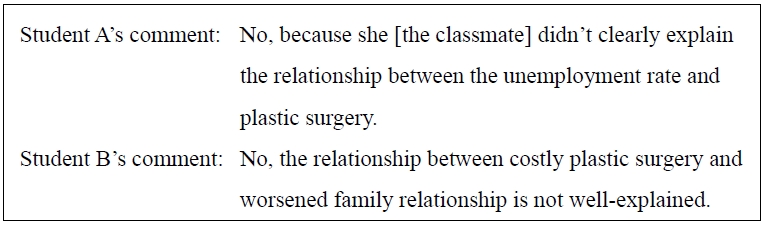

In the online feedback session, teachers showed two arguments that opposed the ban of plastic surgery by looking at the higher employment rate and patients’ poor relationships with families and friends. The teacher then led students to evaluate if each argument was convincing, and if not, which part was not convincing enough, enabling students to think logically and critically. Picture 8 below shows two students’ feedback given on the arguments:

Picture 8 Students giving comments on whether an argument is convincing in the online lesson (edited and retyped) |

Impact

Curriculum level

The incorporation of Bloom’s Taxonomy, the PEEL framework for writing and enhanced assessment and feedback practices provided a clear and progressive structure to build up students’ higher-order thinking skills and self-evaluation capabilities. Through strategic design of tasks that promoted critical thinking, detailed planning for writing and speaking as well as reflective learning, the learning capabilities of more able students have been further stretched. In addition, teachers may also adopt these strategies in other levels to enhance vertical and coherence of the school English Language curriculum.

Student level

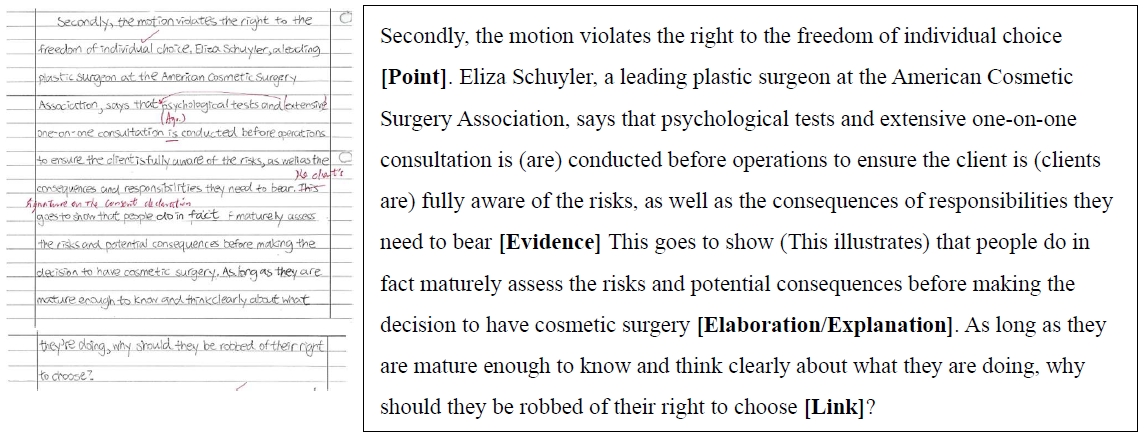

Students’ understanding about and application of PEEL was consolidated, as shown in Picture 3 and another piece of student work (see Picture 9):

Picture 9 A student applying PEEL in writing the debate speech (edited and retyped)

Teachers’ written comments on the body paragraphs of students’ debate speeches and their observations on students’ performance in the examination also revealed that students could apply the strategy in writing. A teacher commented that students could give examples as evidence, one important element in PEEL, to back up their viewpoints in the debates. Students’ thinking skills were also enhanced as shown in the debates and the online writing conference. Students became more conscious of the logical flow of their own and others’ arguments.

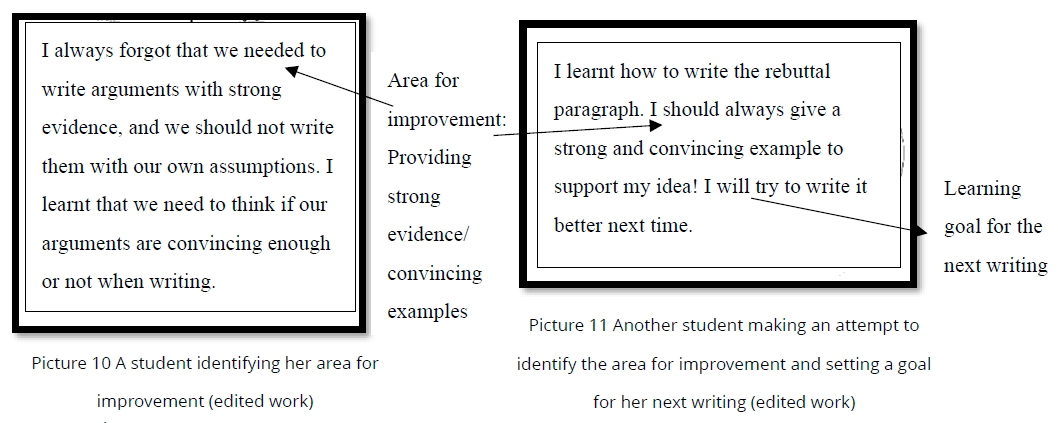

Moreover, students have become more reflective in the learning process. Writing a short self-reflection enabled students to evaluate their own learning progress and set further learning goals. As shown in Pictures 10 and 11, the two students wanted to improve their arguments by making them more convincing, which also became one of the students’ goal in her future writing (see Picture 11).

Teacher level

Teachers became more reflective language teaching professionals in the project. In co-planning meetings, teachers exchanged innovative ideas and teaching strategies (e.g. the “I think, I see, I wonder” approach) to enhance student learning. Using Bloom’s Taxonomy to guide planning, teachers could design tasks and activities of different complexity levels, and be more aware of catering for learner diversity (e.g. students’ interests) in material design. Teachers’ assessment literacy was also enhanced as a wider range of data from assessments were collected for teachers to inform learning and teaching.

Conclusion

While the strategies were effectively tried out in the S4 English Language curriculum to enrich the knowledge and generic skills for the more able students, the school may consider developing the curricula of other levels in both breadth and depth through adopting an even wider range of assessment modes (e.g. helping students build up individual writing portfolios), setting more concrete goals based on their strengths and areas for improvement, and further sharpening their skills in critically evaluating different viewpoints. Through increasing the level of challenge and activating students’ thinking, the potential of different learners can be maximised.

Bibliography

Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved 29 July, 2022, from: https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/

Center for Learning Experimentation, Application, and Research (n.d.). Using taxonomies to create learning outcomes and assessments. University of North Texas. Retrieved 29 July, 2022, from: https://teachingcommons.unt.edu/teaching-essentials/assessment/using-taxonomies-create-learning-outcomes-and-assessments

Centre for Learning and Teaching. (n.d.). Writing paragraphs. The University of Newcastle. Retrieved 29 July, 2022, from: https://www.newcastle.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/333766/LD-Paragraphs-LH.pdf

Costello, C. (n.d.). Peel paragraph writing. Virtual Library. Retrieved 29 July, 2022, from: https://www.virtuallibrary.info/peel-paragraph-writing.html

Curriculum Development Council. (2017). Booklet 4: Assessment Literacy and School Assessment Policy. Secondary Education Curriculum Guide. Hong Kong: Author.

Lam, B.H. (2013, June 28). Formative feedback. The Education University of Hong Kong. Retrieved 29 July, 2022, from: https://www.eduhk.hk/aclass/Theories/Formativefeedback_28June(revised).pdf

St. Clare’s Girls’ School

Janet HO (Language Support Officer)